Gordon Sams (1924 – 2023)

Gordon Sams died last week, just a month after he turned 99. One of the hazards of living a long time is that you sometimes outlive people who remember why you were important. Sams was notable in Knoxville history for several seemingly unrelated and even incompatible reasons. He was a U.S. Navy combat veteran of World War II. He was a public servant, and a name recognizable on ballots, when he was Knox County Register of Deeds for nine years, and later chair of the Tennessee Housing Development Agency, which helped open opportunities for homes for those who might otherwise have trouble affording them. He ran an advertising agency and dealt in real-estate development. He took care of a family with unusual challenges.

Gordon Sams died last week, just a month after he turned 99. One of the hazards of living a long time is that you sometimes outlive people who remember why you were important. Sams was notable in Knoxville history for several seemingly unrelated and even incompatible reasons. He was a U.S. Navy combat veteran of World War II. He was a public servant, and a name recognizable on ballots, when he was Knox County Register of Deeds for nine years, and later chair of the Tennessee Housing Development Agency, which helped open opportunities for homes for those who might otherwise have trouble affording them. He ran an advertising agency and dealt in real-estate development. He took care of a family with unusual challenges.

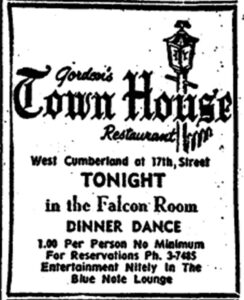

However, he’s also a legend in local jazz—and for a reason that’s relevant to the current discussions of the fate of Cumberland Avenue. In early 1958, on that street that had previously been a mainly practical place of pharmacies, hardware stores, and tire stores, Sams opened a landmark nightclub. Gordon’s Town House, located at the southwest corner of 17th Street, was a jazz club. The large Falcon Room was for big events; the smaller, more intimate Blue Note venue was mostly for local talent.

Big names played at Gordon’s. He’d been a jazz fan since the 1930s. One of the high points of his youth was seeing, up close, young Frank Sinatra sing with the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra at UT’s Alumni Auditorium in 1941. He was the last living person I know who recalls that show, which was amazing by all accounts.

He got involved in the music business, meeting Louis Armstrong at the old Vine Avenue Worker’s Club. He booked shows, made connections, and got to know a lot of the industry big shots, like “Col.” Tom Parker. Even in retrospect, Gordon was happy to admit that he was much less impressed with Elvis Presley than Parker was.

By early 1958, he was ready to open his own place, thinking that corner near rapidly growing UT would attract smart kids to the sophistications of jazz. Big names played there, and most of them drew crowds.

Stan Kenton performed there in 1959 and 1960. Duke Ellington was there in 1959. Count Basie and his orchestra performed there a few times in the early 1960s. Tony Pastor was there in 1962. Woody Herman performed there with his orchestra several times, during the period he was also a semi-regular on the Ed Sullivan show. In addition, the Town House, with its more intimate Blue Note room, was a home base for several local jazz and blues performers, including Charley Boyd, Rocky Wynder, Lance Owens, Willie Gibbs and the Illusionaires, and the Giants of Jazz, including a young UT music teacher named Bill Scarlett, on sax. It could be regarded as the public birthplace of UT’s redoubtable jazz program.

But it was also a restaurant, known to many patrons for its daytime attractions, like bridge tournaments and nonprofit fundraisers.

But it was also a restaurant, known to many patrons for its daytime attractions, like bridge tournaments and nonprofit fundraisers.

Its heyday may have lasted for only four or five years, but it was probably Knoxville’s coolest jazz club in history. As far as I know, it was also the first live-music nightclub on West Cumberland. Although it was probably a good deal more elegant than any club that followed—in 1958, people still dressed up to go out–Gordon’s Town House could be called the juggernaut that made the Strip notable for live music clubs in the decades to come.

It was also, albeit very quietly, unsegregated. At a time when we assume all Southern restaurants and bars followed strict racial codes, Gordon’s did not. Audiences tended to be mostly white, but friends of the performers were often seated among them.

If it were still standing, the Town House would be a historic spot. But after a devastating fire and a redirection of 17th Street in the mid-1960s, no part of it remains.

I first heard of Gordon’s Town House about 25 years ago, via surprising stories told me by people older than my parents. All the people I knew who remembered it died. I just assumed that Gordon was no longer with us. So I was surprised to learn, a few years ago from saxophonist Tom Johnson, that Gordon Sams himself was still alive, and often in a mood to reminisce. I much enjoyed our long conversations, and Gordon was happy to make the rumors of the Town House something more than a legend.