David Chapman Father of a National Park

CROSS THE HENLEY STREET BRIDGE over the Tennessee River and you will be on Chapman Highway headed south towards the Great Smoky Mountains. The highway honors a community leader, a civic booster, and prominent wholesale druggist whose firm was a Knoxville fixture for several years, but who, during that time, accomplished something extraordinary on a national level.

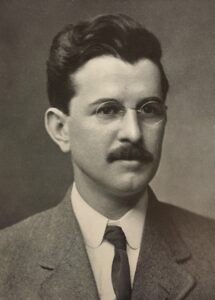

David Carpenter Chapman (1876-1944) is known within the pages of regional history as the “Father” of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. In honor of the tireless efforts to help establish the park, Mt. Chapman, one of the 10 highest mountains in the Appalachians, bears his name. Chapman was fearless in his attempts to make the national park a reality, and through sheer dogged determination he was ultimately successful in helping acquire 6,600 individual tracts of land to establish a national park that now serves more visitors than any other national park in the country.

David Chapman was born to John Ellis Chapman (1847-1900) and Charlotte Alice Young Chapman (ca. 1853-1928) in Knoxville on August 9, 1876. Originally from Anderson County, David’s father first went into business in Clinton, Tenn. with the wholesale firm of Carpenter, Ross & Lockett before moving to Knoxville. He established Chapman, White & Lyons, a wholesale drug firm, with local business partners in 1882. Like his son after him, John Chapman was a prominent name in community affairs, most notably as one of the founders of the Knoxville Board of Trade (later renamed the Chamber of Commerce). He was also involved in the 1897 state centennial celebration in Nashville, including the erection of the Knoxville Building, which came back to this city as the Woman’s Building on Main Street.

David’s mother, Alice Young Chapman, grew up on a farm at Eagle Bend, close to Clinton, Tennessee. She was active in civic and religious efforts, serving as President for the Methodist Women’s Home Missionary Society. She maintained a summer cottage in Eagle Bend, but in the early 1920s, 20 years after her husband died, used her wealth to travel extensively around the world. Her travels included time in Paris as well as in Rome, where she stayed with her old Kingston Pike neighbor, Eleanor Deane Swan Audigier, a patron of the Knoxville art scene, who had moved there with her new husband Louis Bailey Audigier, a former managing editor of the Knoxville Journal who took on a grander assignment as a foreign news photographer for the New York Times. Mrs. Chapman made subsequent trips to Egypt and the Middle East, where she became seriously ill in Jerusalem, before moving on to Asia. While visiting China, she broke away from her tourist trip to become involved in mission work, and lived there for two years. On her return to Knoxville, she gave public talks about China and its people. Mrs. Chapman died in 1928.

When David was born, the family lived on the northwest corner of Fifth Avenue and Deery Street (the house is long gone). The Chapman house was a short walk to the Peabody School, a public school (still standing on Morgan Street today and now occupied by the Democratic Party Headquarters). Born into a wealthy family meant that some of the lad’s youthful accomplishments were highlighted in the local society pages. In 1886, while in second grade at the Peabody School, a map that he drew of Knoxville received some acclaim. Later, at another school on Fifth Avenue he won a prize for a poem entitled, “My Lost Youth.”

At a YMCA picnic at Perez Dickinson’s Island Home in South Knoxville, the 11-year-old won a baseball for his feats in the long jump competition. Later, Chapman spent time at Baker-Himel, a private Knoxville prep school for boys on Highland Avenue. Before he went to college, he was schooled in North Carolina for a time.

***

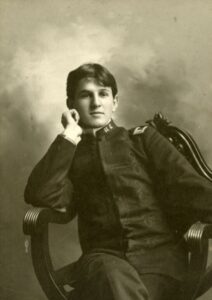

At 18, Chapman enrolled at the University of Tennessee during the Charles Dabney administration, and he excelled on the playing field, winning honors in football, baseball, and athletics. The Knoxville Sentinel reported that “Dave was one of the pluckiest, nerviest quarterbacks that ever wore a University of Tennessee uniform.” (Of course he was one of the first.) He also served in the UT Cadets along with future Fire Chief Sam Boyd. In 1894, Chapman won a medal for best rifle shot.

An active member of Sigma Alpha Epsilon, Chapman represented the fraternity’s UT chapter at a national meeting in St. Louis, at which President McKinley, a member of that fraternity, also participated. Chapman’s fraternity brothers included future Knoxville businessmen Cowan Rodgers and Cary Spence.

In 1897, he served as a business manager for the first-ever Volunteer Yearbook. Within weeks of the yearbook’s publication, he decided to end his studies before graduation to pursue business interests. Before too long he would join his father’s firm.

Out in society, Chapman joined his chums in the fall Carnival that year, playing a part in a “Grand Historical Ball” at Staub’s Theatre, the closing feature of the three-day festival. The “Founding of Knoxville” was the ball’s central theme, including a “tableau” of the Treaty of Holston of July 1791 where the governor of the Southwest Territory, William Blount, met with Cherokee Chiefs to establish a peace treaty. Chapman himself took part in the costumed finale, an 1830s dance entitled “Sir Rogerly Coverly” (based on the fictional English country gentleman, Roger De Coverly) and shared in the collective glee following a congratulatory telegram from President McKinley (whom he may have met in St. Louis with his fraternity brothers).

Later, the Chapmans moved to “Cherokee Place,” a grand 26-room home on Kingston Pike near where Second Presbyterian Church stands today. The house was likely named to tie in with the Cherokee Bridge near the house as well as the planned, but never built, upscale residential development also named Cherokee across the river (now Cherokee Farm). Following his father’s death, David Chapman sold the house to railroad contractor William Oliver in 1902. Oliver served as President of the 1910 Appalachian Exposition and hosted two visiting U.S. presidents at that house, William Howard Taft and Theodore Roosevelt, during their respective visits to Knoxville. (The house was demolished in 1941 due to high taxes and costly repairs.)

***

David Chapman’s military career began with the Spanish-American War in the spring of 1898 when he joined the army, serving as lieutenant of the Third Tennessee Infantry stationed at Chickamauga, Ga., and Anniston, Ala. He was swiftly promoted to aide de camp for Brig. Gen. L.W. Colby (veteran of the Civil War and American Indian Wars). Later Chapman was promoted to brigade adjutant general. Although Gen. Colby’s regiment saw active service in Cuba during the Spanish-American War, Chapman didn’t make it to the front, remaining stateside during the conflict. By the spring of 1899, he returned home, serving as adjutant of the Third Tennessee Regiment.

***

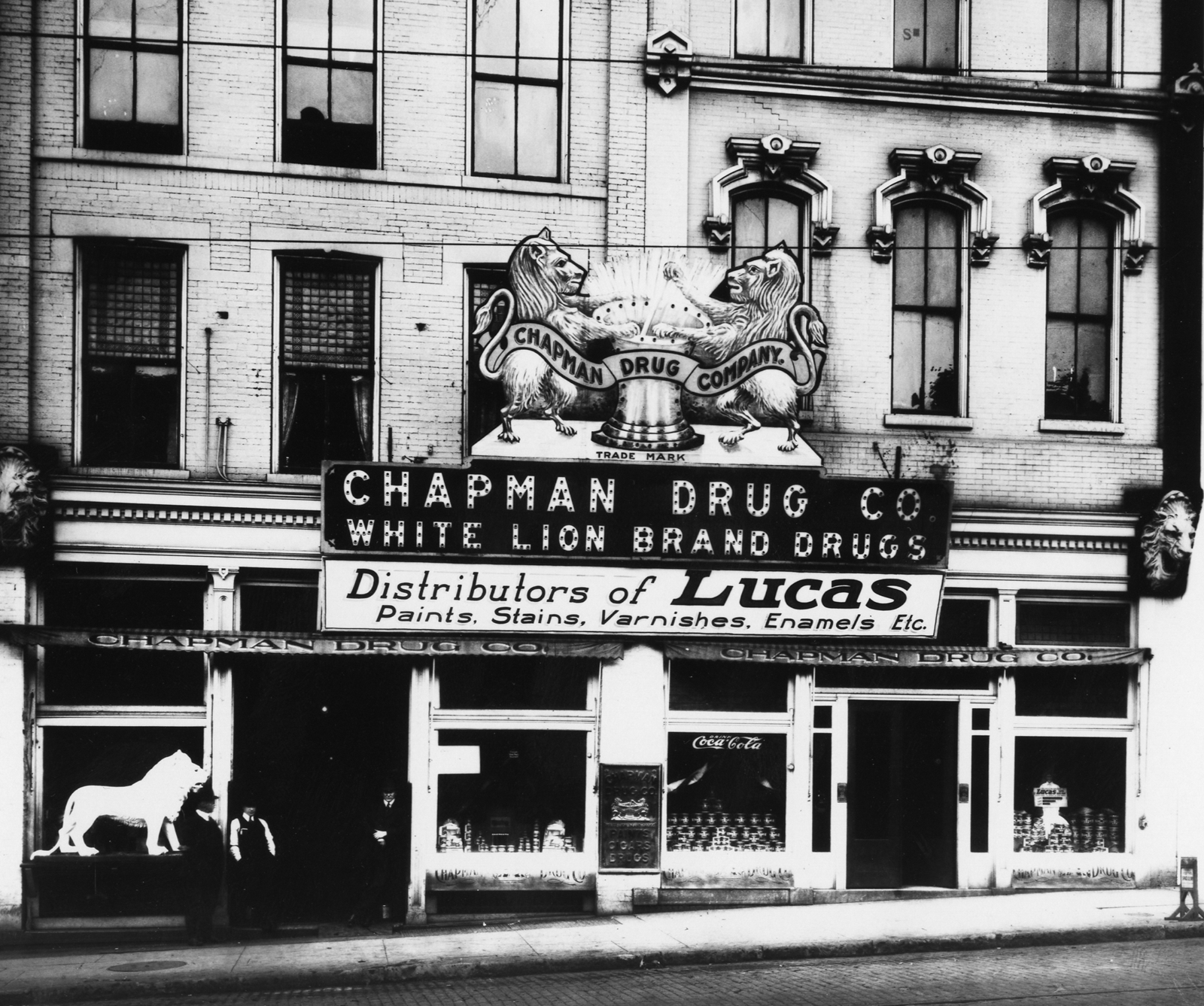

In 1900, the same year that his father died, Chapman joined Chapman, White & Lyons, and rose quickly within the ranks. In time he was able to buy out the interests of the other partners and by 1907 the business was renamed Chapman Drug Company. His grandfather, Judge D.K. Young, remained President until 1912, when Chapman took over. The company didn’t restrict itself to wholesale pharmaceuticals. According to one ad, Chapman sold “candles, dolls, stationery, Christmas novelties, and fireworks.” The firm also served as the local agent for Royal Amber Ginger Ale. For years, a statue of the company’s trademark “White Lion” stood in the window of the Gay Street store and later on State Street, where the company moved in 1923.

***

In the early 20th century, David Chapman’s business interests extended beyond his wholesale drug company. He served as a director and stockholder with City National Bank, and C.B. Johnson Publishing Company (publisher of the Knoxville Sentinel). He was a community leader, notably as President of the Knoxville Board of Trade, and a founder and first president of the Knoxville Rotary Club, founded in 1915. He was also an active member of Cherokee Country Club, the Cumberland Club, and the Appalachian Club at Elkmont in the Smokies, the cluster of privately owned cabins that grew out of the former logging town, and served as an exclusive resort for affluent Knoxvillians.

As a committed civic booster, he was a chief advocate for a proposed “East Tennessee Exposition” planned for the fall of 1903 at Chilhowee park. The vision for the exposition was to “give to this city and section an advertisement that will result in a rapid development of our great and varied resources—the utilization of the latent wealth of this favored region.” In his mid-20s, Chapman didn’t hold back his feelings on the venture, accusing some local businessmen of “old fogyism” for not supporting an apparent “fail-safe scheme” to raise $20,000 in subscriptions to fund the enterprise.

The idea, which came to naught, may have been ahead of its time. Students of Knoxville history may already recognize the seed of what became, less than a decade later, the highly successful Appalachian Expositions of 1910 and 1911, and the National Conservation Exposition of 1913, all held at Chilhowee Park. Chapman served as a director for all of these successful educational and cultural events. For the 1913 exposition, he also acted as Director of the Reception Committee, welcoming numerous high-profile guests, including Helen Keller and William Jennings Bryan. As part of this engagement, Chapman read out a humorous poem to Bryan who was reportedly very amused.

***

In 1906, Chapman had married a local girl, Anna “Augusta” McKeldin, the daughter of John A. and Salome McKeldin. Her father served as a senior financial official for Knoxville Woolen Mills. Growing up in a wealthy family, Augusta featured frequently on the social pages, as did Chapman. However, the couple held a small, private wedding ceremony at the bride’s parent’s home on West Main Avenue. Following the honeymoon, the Chapmans settled in to a flat at the fashionable Belle Truches apartment building at Henley Street and West Church Avenue. The union was tragically cut short when Augusta died just two years later, at age 28, while visiting relatives in Atlanta. She is buried near her parents in Old Gray Cemetery.

In the wake of his wife’s death, Chapman turned his interests to business and civic improvements. By 1909, he was playing a strong booster role for the “Greater Knoxville” movement, encouraging city leaders and citizens to support the idea of expanding the city’s geographical scope. Central among Chapman’s views was the belief that investment companies across the nation were targeting cities with populations exceeding 50,000. According to Chapman, Knoxville’s population then was 10,000 fewer than that mark. Without the expansion of the city’s population, he argued, Knoxville would have a weak hand in attracting investors, thereby putting the city at a disadvantage compared with faster-growing cities such as Chattanooga and Memphis. Knoxville Mayor Sam Heiskell, for one, was against the idea, and voters made their feelings clear in the August election that year, comprehensively voting it down. Eight more years would pass before the city re-considered such a proposal and voted for a city-wide annexation in 1917.

In 1911, Chapman married again, this time to Sue Ayres Johnston, daughter of Confederate veteran Capt. John Yates Johnston and Susie Ayres Johnston, niece of English-born industrialist and mayor, Joseph Jaques. At the turn of the century, Sue was considered a local “Gibson Girl,” a look popularized by the illustrator Charles Dana Gibson. She and her sister Jane Jaques, through their father’s side of the family, were cousins of Grace Wilson who married Cornelius Vanderbilt of the Biltmore estate in Asheville. A good friend of Chapman’s first wife, she had served as maid of honor at that 1906 wedding.

After the couple’s wedding, the Chapmans sailed to Europe for their honeymoon. The name of the ocean liner that carried them there was the RMS Lusitania. Four years later the Lusitania would be fatally torpedoed by a German submarine off the coast of Ireland while on its way to Liverpool. Of the 1,962 passengers, only 764 survived.

***

During World War I, on the request of Tennessee Governor Tom C. Rye, Chapman reorganized the Fourth Regiment of the National Guard headquartered in Knoxville and was promoted to lieutenant-colonel. By the following year he was generally referred to as Col. Chapman. An early activity led by Chapman involved preparing 950 Christmas care packages for Knoxville area soldiers, including cakes, sweets, cigarettes, tobacco, and a Christmas card.

Meanwhile, Sue Chapman and her sister helped the local war effort by co-founding the “War Work Shop,” at the Park House, on the corner at Cumberland Avenue and Walnut. There, the Red Cross produced first aid supplies, while a knitter from Knoxville Woolen Mill made socks, and a local writer’s group made joke books. Other rooms in the house served as a gift shop and a tea room with profits from sales and membership dues distributed among the Red Cross, the Knox County Soldier’s Relief Society, and the Fatherless Children of France.

***

“View of Mrs. Chapman’s Garden” – a rare glimpse in color of the gardens at Annandale, 1930s. (Knoxville Garden Club Slides, University of Tennessee Libraries.)

In 1919, after living for several years on W. Main Avenue, the Chapmans purchased a 500-acre farm on Maloney Road that overlooked the Tennessee River and extended east to Old Maryville Pike, part of the old Maloney family property.

The Chapman house, described as a “great rambling white house,” by the Knoxville News-Sentinel, included sections dating to the early 1800s. At the time, the location may have been considered remote, though it would be more convenient for Chapman’s future visits to the Smokies. The couple named the property Annandale, apparently for Sue Chapman’s father’s home in Loudon County, in turn named for an ancestral home in southern Scotland.

In 1923, Chapman purchased a former Kentucky racehorse, “Bourbon Pates” to ride on his property, but it appears the interest was short-lived. Meanwhile, the Chapmans, who had no children, began developing Annandale as a natural showplace.

The garden was well described in a 1932 article in the Knoxville News-Sentinel, during a spring meeting of the Knoxville Garden Club. Flowers planted alongside the Maloney Road property line greeted visitors for almost a mile up to the entrance. The driveway itself was lined with yellow jonquils and blue hyacinths while behind the house were tiered gardens lined with stone and filled with poppies, rock gardens filled with ferns and moss, and a plum tree orchard. A French-style “allée,” lined with cedar trees with a stone bench at the end provided the Chapmans and their guests with a contemplative spot within the garden.

On at least one occasion, Mrs. Chapman opened the gardens to the general public to raise funds for Blount Mansion where she served as a volunteer. A color slide in the University of Tennessee Libraries’ Special Collections captures the beauty of the Chapmans’ garden in the early 1930s.

In 1933, a devastating fire tore through the house. Given the location of the property, outside of city limits, the fire brigade struggled to adequately fight the blaze, which destroyed the home, leaving only one chimney standing. Efforts to remove much of the Chapmans’ antique furniture collection was successful. However, it’s likely that many other treasures may have been lost in the fire. The Chapmans were known to have collected old silhouettes of past U.S. Presidents, including Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Jackson, and James Madison. Another one, of William Blount, was donated to Blount Mansion before the fire. The Chapmans never again lived on the property. Instead, they moved in with Mrs. Chapman’s sister nearby on Topside Drive.

***

The Great Smoky Mountains National Park movement emerged in 1923 following the suggestion by Mrs. Annie Davis, wife of industrial Willis P. Davis, that the Great Smoky Mountains would be an ideal location for a new national park in the eastern United States. Few would have envisaged that Mrs. Davis’ candid quip, “Why can’t we have a national park in the Great Smokies?” after visiting the majestic national parks out west, would lead to a 17-year movement that would require hundreds of volunteers and millions of dollars to create the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

That David Chapman has been referred to as the “Father” of the Smokies movement speaks volumes about his leadership and dedication. It is fair to say that without Chapman’s unwavering refusal to give up on the idea, following a rollercoaster ride of highs and lows throughout the years, there would be no park—perhaps at best a national forest.

By serving on numerous business boards and civic committees, Chapman was well-placed to become intimately involved in the movement, although like others he was initially less than inspired by the idea. Rather, he later confessed, he hadn’t even recognized the mountains’ rugged nature as anything truly remarkable.

However, at the newly formed Great Smoky Mountains Conservation Association’s inaugural meeting in late December 1923, Chapman was present as a member, just as he was with numerous boards and committees.

Carlos Campbell, then assistant manager of the Chamber of Commerce, later acknowledged that Chapman “had hunted and fished all up and down Little River, and spent much time at the Elkmont summer colony, and that he knew it was a beautiful country, but never dreamed of it being unusual or distinctive.”

Chapman still wasn’t stirred until he visited Lawson McGhee Library to read a copy of President Theodore Roosevelt’s 1902 report on the Southern Appalachians: “Message of the President of the United States: Transmitting a Report of the Secretary of Agriculture in Relations to the Forests, Rivers, and Mountains of the Southern Appalachian Region.” Chapman was now more than impressed.

The report, more than 20 years old when Chapman read it, discussed the benefits of national forest preserves rather than national parks. But the message, and the messenger—conservationist-minded President Theodore Roosevelt—may have doubly resonated with him because it not only officially recognized the beauty of the Smokies and other natural areas, but also assigned economic value to them.

In its leading statement, Roosevelt wrote, “Hence it is that in this region occur that marvelous variety and richness of plant growth which have led our ablest men and scientists to ask for its preservation by the Government for the advancement of science and for instruction and pleasure of the people of our own and of future generations.” He concluded by emphasizing that “Federal action is obviously necessary, is fully justified by reasons of public necessity, and may be expected to have most fortunate results.” In the 1920s, when Chapman read the report, the concept of a national park in the east, and its inherent benefits for the region, including Knoxville, must have appealed to him rather than a national forest, which those still connected with the lumber industry viewed as a more lucrative goal.

After reading the report Chapman became converted to the cause. By the following year, he was using his leadership positions—he was by then director of the Dixie Highway Association—to talk openly to groups about the national’s park potential and benefits for the region.

In the summer of 1924, Chapman made what may have been one of the most pivotal actions of the entire park movement. He sent the Great Smoky Mountains Conservation Association’s official photographer, the renowned Knoxville photographer Jim Thompson, to Asheville’s Grove Park Inn. With a carload of his superlative photographs of the Smokies, Chapman intended to sway the opinion of members of the Southern Appalachia National Park Commission charged with deciding on the next national park in the eastern United States. At that moment the Commissioners were heavily leaning towards the Grandfather Mountain-Linville Gorge area of North Carolina as the preferred site and did not even plan to visit the Smokies. Thompson’s photographs stopped them in their tracks enough to schedule a trip to the Smokies to see for themselves the natural grandeur stunningly captured in Thompson’s portraits.

The logistics of the Commissioners’ trip the following month to the Smokies fell to Chapman who met them, along with a team of filmmakers with the Keystone Movie Company, at the Farragut Hotel on Gay Street. On the recommendation of a friend, he hired a young Knoxvillian named Paul Adams. Along with a few Gatlinburg natives, Adams would lead the group up majestic Mt. Le Conte via Rainbow Falls and down by way of Alum Cave. At this time though, trails were barely established and the trip proved challenging for all members of the hiking party. W.P. Davis himself fell on the trip and required assistance to help him down off the mountain. Nevertheless, the expedition was a major success and helped the Smokies on their way to being chosen as the site of a new national park. Still, there was much yet to do. Reflecting back on that trek years later in his self-published memoir, Paul Adams considered Chapman “a man of great integrity and fortitude and one who could achieve whatever he set his heart to do.”

Following a commitment in 1925 for the state of Tennessee to purchase 76,507 acres from the Little River Lumber Company, which had felled much of the virgin forest in the Smokies, the national-park effort reached a tipping point. Annie Davis, who had originally sparked the Smokies movement back in 1923, introduced the bill in early 1925 as a rare female member of the Tennessee legislature. That bill was initially turned down following fierce support from an anti-national park faction, but passed on the second time around, aided by a successful train excursion, funded by the Knoxville Chamber of Commerce, for members of the legislature and state officials to witness for themselves the beauty and potential for a national park in the Smokies. Annie Davis was subsequently known as the “Mother” of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

The day after this announcement, Chapman was appointed by Tennessee Governor Austin Peay to serve as the East Tennessee member of the Tennessee State Park and Forestry Commission, charged with acquiring park acreage. Chapman would soon become chairman of the commission.

Later that same year, the Great Smoky Mountains Conservation Association and its counterpart in North Carolina embarked on an ambitious fundraising campaign urging members of the general public to contribute to the effort. At the outset of the campaign, Knoxvillians contributed $100,000 in two days. Chapman himself was an early donor to the campaign, personally contributing $5,000. In addition, he secured pledges from some of the companies with which he was associated.

A bill was introduced in U.S. Congress providing that the Great Smoky Mountains National Park could be “taken over for administration” when a minimum of 300,000 contiguous acres had been acquired. Chapman protested, claiming the goal was too high and was successful at having it downgraded to 150,000 acres. That bill was successfully signed into law in May 1926.

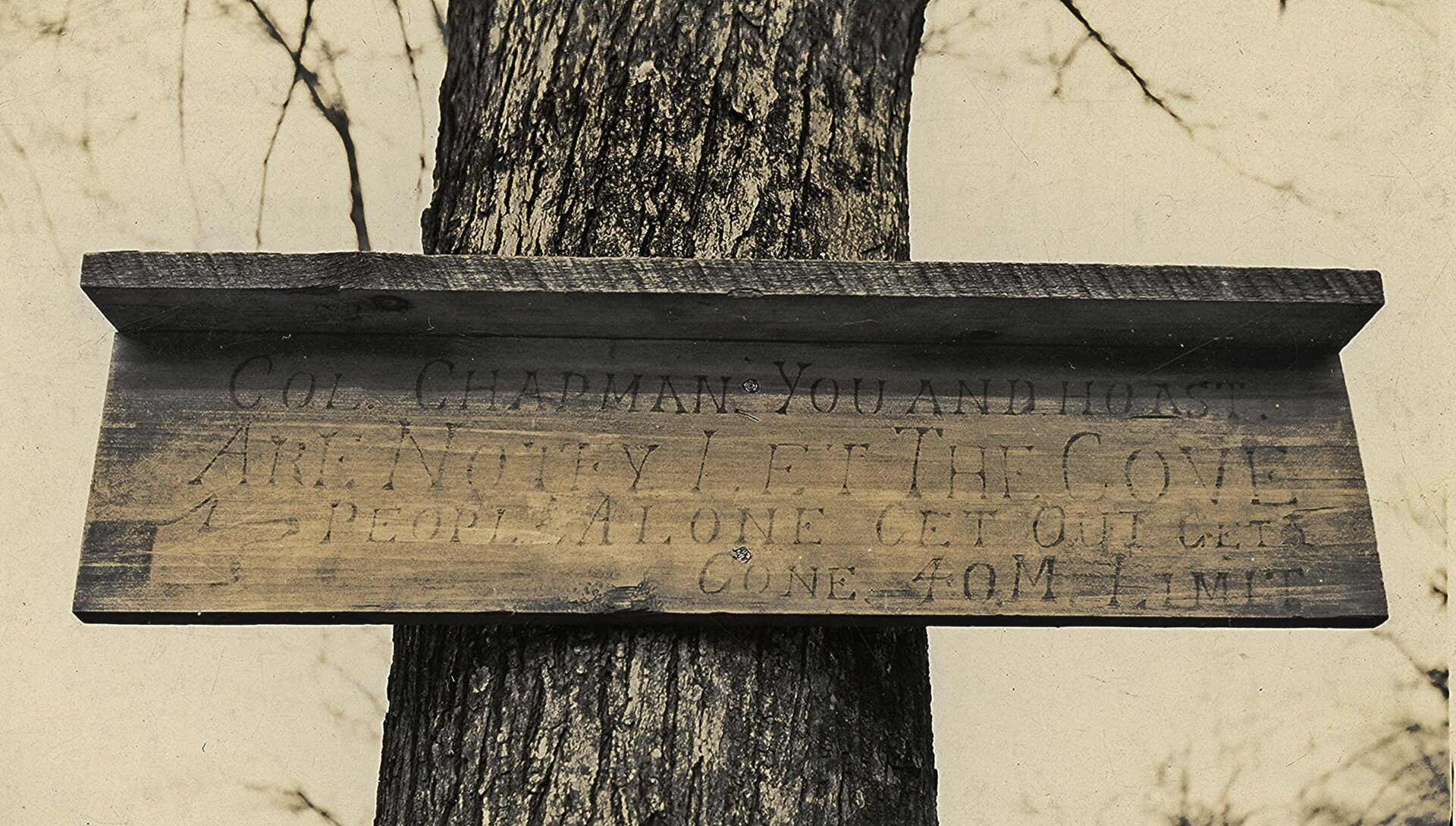

The creation of the national park displaced many mountain folk from their homes. For some who refused to be budged from their ancestral lands and homesteads, bitter feelings ran deep against the “government men” leading the efforts. Col. Chapman, involved in so many land acquisitions for the park, proved an obvious target. He received personal threats from deeply entrenched Cades Cove residents, with one anonymous telephone caller warning the Colonel that he “might spend the next night in hell.” On a visit to the Cades Cove area, Chapman brought back a crude sign that had been left for him by some mountain folk nailed to a tree near the Missionary Baptist Church (today located on the Cades Cove driving loop). The threatening sign read:

“COL. CHAPMAN YOU AND HOAST ARE NOTIFY LET THE COVE PEOPLE ALONE. GET OUT. GET GONE. 40 M. LIMIT.”

The “40 M. Limit” meant for Chapman and his cronies to stay 40 miles away from the Smokies. Undaunted, Chapman persisted. Later, after the national park had become a reality, the sign became a treasured souvenir.

Despite Chapman’s idealist goals, the fact remained that many families, and indeed entire communities, were forced to leave the Smokies. Landowners were offered two options by the Park Commission: to sell at full market price, or sell at a lower price with the right to live in their homes on a lifetime lease. For those who held out the longest, it was a bitter price to pay.

Meanwhile, in Knoxville and elsewhere, school children donated pennies and dimes to the cause, with Chapman playing a pivotal role in securing the largest and most important gift to the park campaign. He helped Arno Cammerer, then assistant director of the National Park Service, to solicit a substantial gift from John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Chapman forged a trusting relationship with Cammerer during his many trips to Washington, D.C. and New York on park business. Cammerer, himself, publicly commended Chapman for selling the gift idea, and the cause, to Rockefeller. Rockefeller was duly inspired and gave an inspirational $5 million dollars, which served as a matching gift that finally helped the Smokies become a certainty. Late in life, Chapman recollected, “I guess the biggest kick I got out of the whole thing was when I learned we were going to get that $5 million.” Cammerer had called him to Washington and told him personally about the extraordinary gift, given in memory of Rockefeller’s mother, Laura Spelman Rockefeller. Chapman was thrilled, but had to sit on the news for six weeks before he could tell another soul. The wait “nearly killed me,” he later quipped. Rockefeller’s gift was officially announced on March 6, 1928.

The success of the Smokies movement was due to Chapman’s close ties with the leaders of the National Park Service, as seen here with Horace Allbright, NPS director (left) and assistant director, Arno Cammerer. (McClung Historical Collection.)

By 1932 though, changes were made to the State Park Commission. Chapman remained on the board, but was joined by several others, including two other Knoxvillians, George Dempster and James Trent. Trent had just served as mayor of Knoxville the previous year; Dempster, who would soon invent the Dempster Dumpster, was city manager. Chapman and Dempster notoriously butted heads on the commission.

At a meeting in the Burwell Building on January 9, 1933, Dempster accused Chapman of lying over a land acquisition report. A fist fight, which witnesses described as “furious,” ensued. According to the Knoxville Journal the next day, the 57-year old, diminutive Chapman removed his glasses and grabbed Dempster by his tie and thumped him in the face. After a quick tussle, Dempster recovered enough to assume the advantage. The Journal provided a blow-by-blow description of the fight as “Dempster held Chapman’s bushy gray hair with one hand and pounded him in the face with his fist.” Watching the altercation close at hand was Charles J. Brown, manager of Pryor Brown Parking Garage, who said, “Let ‘em fight: this is one fight I want to see go on!”

The fray ended almost as quickly as it had begun, with Chapman faring much worse than his younger, larger opponent sustaining broken ribs, a black eye, severe bruising, and missing a gold-inlaid tooth. Dempster was only winded and had a small cut on his wrist, but his necktie was so tight around his neck that it had to be cut off. He rebuffed Chapman, saying, “You won’t have to hire anyone to fight me. I’m one man you can’t run.” Chapman apologized before retreating to a washroom to clean the blood from his face. Later in the day, a newspaper reporter found Chapman’s gold tooth on the floor and returned it to him. The incident was one clear instance when Chapman’s own motto, “Hit them first,” served him poorly.

***

Thanks to Chapman’s efforts, the first transfer of land to the Government was made in early 1930 and unofficially marked the establishment of the national park, even though it wasn’t until 1934 that the park officially opened.

Carlos Campbell saluted Chapman with another memorable quote, “It was the scrappy colonel who refused to give up the fight when, at so many times, it seemed hopeless.”

In the late 1930s, Chapman received two distinctions recognizing his efforts to establish the Great Smoky Mountain National Park. In 1931, the United States Geographic Board conferred the honor that a Smoky Mountain peak, the fourth highest peak in the Smokies (6,450 feet) be named Mt. Chapman after him.

The second honor came in 1937 when the Tennessee Legislature passed a bill naming a road after him in honor of all his efforts to establish the Great Smoky Mountain National Park. Thus, the southern route of Highway 441 from Knoxville to Sevierville was named Chapman Highway.

Chapman was also gifted a cabin in Elkmont by the National Park Service at some point during the 1930s. Although many of the cabins have been demolished, the Chapman-Byers cabin (it was later transferred to his brother-in-law Rufus A. Byers) has been retained on “Society Hill” in the Elkmont Historic District, a.k.a. the Elkmont Ghost Town, established in 1994.

***

Although the Great Smoky Mountains National Park officially opened 1934, the culmination of the park movement for leaders like David Chapman came with the dedication of the park, attended by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1940. By this point, Chapman, now in his mid-60s, was still involved in a wide range of civic affairs, if perhaps not engaged at the same intensity that he once was. As “Father of the Park” he was asked to serve on committees such as the Great Smoky Mountains Festival in 1941 and the same year was awarded a certificate for being the first honorary member of the Knoxville Journal’s Junior Historical Society. For years he presided over many local events and receptions for dignitaries visiting the Smokies.

In 1942 Chapman was still active and recruiting for the Fourth Tennessee Regiment, but at age 66 his health began to fail. In early 1944, he suffered a heart attack followed by a series of strokes that would leave him hospitalized for months. After rallying, he enjoyed a daily car ride downtown from home or St. Mary’s Hospital. Just shy of his 68th birthday, Chapman died on July 27, 1944. The Knoxville newspapers were quick to acknowledge his passing and recognize his contributions both within the city and across the Smokies.

Following a funeral service at St. John’s Episcopal church, David Chapman was interred at Highland Memorial Cemetery in Bearden. Among the pallbearers were former Knoxville Mayor Ben Morton; Ross Eakin, superintendent of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park; Alfred F. Sanford, publisher of the Knoxville Journal; and fellow Smokies advocate Carlos Campbell. As a mark of respect, Blount Mansion, where Chapman’s wife Sue had once volunteered during its early days as a museum, closed for the day.

The Knoxville Journal remembered him fondly as a friend to Knoxville, “He was a good man to know, as a cordial, intelligent citizen of good will. He lived in Knoxville all his life and counted his friends by the hundreds…”

Today, rather like his company’s white lion once did, Chapman remains a permanent icon on Gay Street. Visit the lobby at the East Tennessee History Center, and there you will find a life-like bronze bust of Chapman by Hungarian artist Lajos Biro, commissioned by the Rotary Club of Knoxville to sculpt the piece for its centennial year in 2015. Compared with photographs of Chapman, the bust accurately captures his likeness, and it’s a fitting testament to a well-respected community leader and “Father” of the Smokies who achieved so much for the city and the region.

By Paul James