Christmas 1918

Again the White Lights Winked

by Jack Neely

December 18, 2018

Your friend Kumbak, a Mysterious Squadron, and Knoxville’s Niagara: We remember a Knoxville Christmas exactly one century ago.

One of downtown’s most popular department stores in 1918 was S.H. George & Son—George’s, to you and me. They were all about Christmas. Their ads grabbed you by the collar. “Mr. Man! Your wife wants an umbrella!”

Extract from George’s advertisement, Knoxville Journal, December, 1918 (McClung Historical Collection)

On the third floor of George’s, at Gay and Wall, was a peculiar department called the Japanese Pagoda Tea Shop. It was the era when America was mad for all things Asian, tea, kimonos, crepe de chine, Japanese gardens, silk Japanese umbrellas, Sessue Hayakawa movies (there were about seven of them on Gay Street that year). There was even a Japanese Tea that December at the Women’s Building, to which attendees were encouraged to wear Japanese costumes. They sang Japanese songs and looked at Japanese pottery.

There in George’s exotic little Japanese Pagoda department was a figure never before seen in town. “He is oriental, in all his solemn dignity,” George’s announcement said. “He sits, Buddha-like, with folded hands.”

He was a figure made of bronze. Printed alongside him was a little poem.

My name is Kumbak, I’m your friend

And this will be my prayer

That you shall see the one you love

Come Back from Over There.

Christmas of 1918 came with that one awful fact, rarely directly addressed. No one knew for sure who was coming back, whom it was safe to shop for, and what they might need, and whether an umbrella, a football, or an artificial leg. The Armistice had been more than a month ago, greeted with wild celebrations by thousands in the streets of downtown. But those who had cheered back on Nov. 11, gleefully hanging effigies of the kaiser from lampposts on Gay Street, hadn’t yet reckoned the final costs of the war. Most of America’s serious losses, war deaths and serious injuries, had occurred in the war’s final weeks. More than a month after cheering the victory, the War Department was still releasing lists of the injured, the seriously wounded, the missing in action, and the dead.

During the Christmas shopping season, during Christmas week, and into the New Year, mothers and wives and children were still getting telegrams that their favorite soldier wouldn’t be coming home.

~~~

War has surprising effects on culture, even when it seems to have no direct connection. That war may have affected how we celebrated Christmas.

A generation earlier, in the Victorian era, many stores opened on Christmas Day. Most people didn’t buy Christmas trees until Christmas Eve, when hundreds of them arrived in great heaps on Market Square. The holiday arrived with a chaos of dangerous fireworks, wacky vaudeville shows, Dec. 25 bowling tournaments, late-night masquerade parties, public binge drinking, gambling, nocturnal pranks, arson, and occasional gunplay.

Maybe it was something about the shock of war that changed things. Or maybe it was dread of the deadly Spanish Flu epidemic, that got people, perhaps subconsciously, to rethink things, reset their expectations, to hunker down at home. By 1918, Christmas was becoming a more private holiday than ever before, something celebrated mainly within the family.

Shopping started earlier than usual, by government request- to avoid wartime transportation tangles that could affect the well-oiled machine that was the American war effort. Some started shopping as early as October. That became a habit.

And contributing to the new privacy of Christmas was the fact that war coincided with a backdrop of prohibition, which began locally with the 1907 saloon ban. By 1918 it seemed to be more effective, because it was national. Prohibition affected even teetotalers. With no legal saloons, there were fewer people out at night downtown, less of a sense of public excitement. Without so many people out drinking, stores closed earlier. By 1918, the whole country was celebrating the holidays more quietly.

The war, the flu, and prohibition also coincided with a more general phenomenon, of the increasing popularity of automobiles, and the recent expansion of Knoxville to include Looney’s Bend, not yet known as Sequoyah Hills, and Lincoln Park, and South Knoxville. In 1918 thousands of people were living out of earshot of downtown’s holiday hallooing.

By 1918, Christmas was starting earlier, becoming less public and more domestic, settling down to be something a lot like what we know today.

Still, if you went back, you could tell the difference.

Christmas trees, mostly cedar, arrived on Market Square earlier than in years past–on Dec. 18, a full week before the holiday. People were just starting to decorate early. With holly and other evergreens, the old market took on “a holiday appearance.”

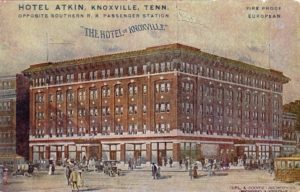

One part of the downtown Christmas as it was known in 1918 may never return. In those days, people came to Knoxville from as much as 100 miles away, from places as far as Kentucky and Virginia and North Carolina, just to shop at the amazing big stores of Gay Street: at Miller’s, at Newcomer’s, at Arnstein’s, at George’s. Many actually booked rooms for several nights at downtown hotels. The new Farragut Hotel wasn’t quite open yet, but the big, swank Atkin on Depot, and the Watauga, and the St. James, and the Colonial had full houses.

Hotel Atkin, vintage Knoxville Postcard, circa early 1900s. (Courtesy of the Sam Furrow Knoxville Postcard Collection)

“The peace so gallantly won by the allied forces on a foreign battlefront stimulated trading in all lines,” according to one reporter. The 10 days before Christmas, 1918, were said to be the biggest retail season in Knoxville history.

For sale that season were mostly practical things, clothes of all sorts, but also velocipedes and Iver Johnson bicycles, pianos, phonographs. Newcomer’s offered Tennessee pearls. The new automotive stores sold all sorts of accessories for the minority of Knoxvillians who owned cars, including robes (cars tended to be very cold in the winter), “trouble lamps” and tire vulcanizers. Ouija boards were big, touted as “the jolliest, most mystifying entertainment.”

Newcomer’s store ad, Knoxville Journal, December, 1918 (McClung Historical Collection)

Stores were perhaps urgently trying to unload the board game Kop the Kaiser, a dice game that “gives children a chance to get even with Bad Bill” by rolling dice and avoiding U-boats.

~~~

Most Knoxvillians had seen aeroplanes before, but they were still so rare that when you saw one you wondered what it was up to. To see three identical planes in the sky at once was extraordinary.

They were at about 2,000 feet, close enough that some savvy folks on the ground could identify them as Curtiss biplanes. They flew over slowly at first, just circling around Chilhowee Park and also Bearden, but then soared onward toward the southwest, never landing. There were reports and rumors about the phenomenon, but nothing confirmed. There was of course no way to reach them. It got around that they might come back, maybe land at Johnson’s Racetrack in East Knoxville, which had hosted the first airplane landings in Knoxville history, but only one plane at a time.

In fact they did return, and commenced some eye-catching stunts, as if to get even more attention. However, as they did, they realized that Knoxvillians couldn’t see them. A pall of coal smoke lay over the central part of the city. Downtown Knoxvillians couldn’t see more than a couple hundred feet into the sky.

Knoxville had no air field in 1918. One of the few places clear and flat enough to land three biplanes was at Cherokee Country Club’s golf course. Knoxville’s first 18-hole golf course, it was just barely outside city limits, but right on the Lyons View streetcar. Hundreds gathered on the golf course, in particular around a long flat strip marked with white flags.

Two men were in each plane, and all six were welcomed as heroes, the gallant crews were U.S. Army officers from all around the country—Chicago, Oklahoma, Southern California—here on a national mission. They reported they had gotten here from Chattanooga in just 90 minutes, almost as fast as a train. They took off again and obliged the crowd with some stunts, descending loops, tailspins, the heart-stopping “falling leaf descent.” But they were here to scout air-mail routes.

In the brave new world of the future, mail would arrive by air, and Knoxville was eager and proud. The first Air Mail service in history had started early that year, connecting New York and Philadelphia and Washington.

Greeted as celebrities, the six young men stayed at the St. James Hotel on Wall Avenue and got to see parts of Knoxville unknown to most Knoxvillians, like the interior of the exclusive Cumberland Club on Walnut Street. Downtown, a Lt. Gay remarked that they’d even named a street for him. Knoxville was “a peach of a town,” he said. Mayor John McMillan greeted them personally. Then an impromptu dinner and dance in their honor at the country club.

They stayed a day longer than expected, due to some engine repairs, all accomplished while their planes sat on the golf course.

(None of them were famous pilots, but Marriott was later a leader in the Civil Aeronautics Administration for Southern California.)

Another modern spectacle in 1918 was hardly less impressive than a squadron of army planes.

The Cheoah Dam, 225 feet tall, was almost finished, A total of 47 miles from Knoxville, and just across the North Carolina line, it’s not even in Tennessee. Still, in 1918, when they had a test spill, as they did that December, it was sometimes called “Knoxville’s Niagara.” It was such a famous spectacle that for several years it was a destination for conventioneers. Anyone spending a week in Knoxville was obliged to behold Cheoah, claimed to be the highest dam in the world. How it belonged to Knoxville, even symbolically, is a little complicated.

It was an early hydroelectric dam built by the Knoxville Power and Light Co. However, the Knoxville area’s biggest electricity consumer was Blount County’s large and growing aluminum plant Alcoa, which owned stock in Knoxville’s privately owned utility, and either then or soon after owned Cheoah Dam.

(It’s still an impressive thing to behold; the landmark that astonished visitors in 1918 served as a setting for the 1993 Harrison Ford thriller, The Fugitive.)

Knoxville’s skyline was changing. Gay Street’s brand-new Farragut Hotel, commenced after the fire that destroyed the earlier Imperial Hotel on the same spot in 1916, was almost finished. It promised live music in the dining room every night, and a dedicated fleet of white taxis that ferried patrons to and from the two train stations. It was due to open Jan. 15.

And on UT’s Hill, the Board of Trustees was projecting a major new building plan to replace the aging brick buildings that still bore the scars of Civil War cannon fire, with a major new administrative and academic building. Dr. Brown Ayres described the options for the public. At 62, and apparently vigorous, he presented no clues that he had only another month to live–or that his sudden death would suggest a name for the project he’d begun work on.

Despite the lure of the quiet, beautiful suburbs, and even in the absence of thousands of young men still overseas, downtown was a thriving place. One five-block stretch of Gay Street supported seven vaudeville and movie theaters (most theaters in 1918 offered some of both). Knoxville had no cineplexes, but so many single-screen cinemas, changing features two or three times a week, that you could see more new movies per month in 1918 than you can today.

At the Strand, on Gay near Wall, was A Perfect 36, Mabel Normand’s latest comedy. “Perfect 36” was a phrase used to describe the number of state ratifications that would be required to pass the 19th amendment, giving women the right to vote. But in the movie, the sly title is a reference to a dress size, and by the standards of the day the perfect female figure. Because the movie included a theme involving nudity, it was edited or censored in some markets; there’s no mention of that at the Strand showing.

Following that, at the Strand, was another controversial film, a tragic sex drama with horse racing as a backdrop. Relatively few silent movies of 1918 were family-friendly. The director of Sporting Life was Paris-born Maurice Tourneur, and it was during a period when he had a 28-year-old assistant named Clarence Brown. Chances are, no one in Knoxville knew that fact, except perhaps Brown’s parents. He would soon try his own hand at directing films.

The Rex advertised “not the biggest house, but the best pictures.” On Christmas Day, they began a two-day run of The Ghosts of Yesterday, a creepy Norma Talmadge mystery. Judging by the posters on Gay Street (Talmadge made six movies that year) the 24-year-old New Jersey beauty was the biggest star on Gay Street. But the Christmas Eve offering at the Strand was The She-Devil, starring dark, fascinating Theda Bara, “the screen’s greatest vampire artist.”

On Dec. 20 and 21, the Strand offered a film called The Kaiser’s Finish. The Rex, on the Miller’s block, which had just shown a wartime classic called Wolves of Kultur about high-tech torpedoes (Chapter 13 of the serial was called “The Huns’ Hell Trap”), advertised a sort of nonfiction epilogue, newsreels of the surrender of the German fleet.

The main feature, though, was The Triumph of Venus, a tale of Greek mythology advertised as “the most beautiful film ever created.” However, the theater advised, “No one under 16 admitted: The subject is too deep to be comprehended by the young mind.”

Most of the live shows were at Staub’s Theatre, the 1872 opera house, or the newer Bijou. At Staub’s was Watch Your Step, the very first musical by “Sgt.” Irving Berlin. It was touted as a “Riot of Color, Dancing, Girls, and Ragtime,” with 50 people on stage. It featured his upbeat song, “Play a Simple Melody.”

Staub Theatre at the corner of Gay Street and Cumberland Avenue, circa 1910s. (McClung Historical Collection.)

Gaston Palmer, the French-born juggler, who at the Bijou juggled dustpans, feather dusters, and cigars, all at once, as if they were rubber balls. A legend in juggling history, Palmer was known for taking risks, and for enjoying his failures humorously, often joking directly with the audience. He was frenetic, unpredictable, often hilarious. Twenty years later, he would be one of the first jugglers to appear on television, when it was mostly experimental. He spent most of his performing career in France, but appeared on Ed Sullivan in 1958, and his last movie appearance was more than 50 years after his turn at the Bijou: in 1969, he was the juggler in the offbeat Katherine Hepburn film, The Madwoman of Chaillot.

After that, the Bijou offered, on Dec. 23-24, a now-obscure musical called A Long Way from Broadway, which likely featured songs from the Cohan Revue of 1916, which included the song “(It’s a long way) From Broadway to Edinboro Town.”

~~~

There were few soldiers in theater audiences. Most of the thousands of Knoxville’s doughboys wouldn’t come home until well into 1919, but at Christmas, 1918, it was estimated that 300 soldiers were afoot in the city, proud to wear their uniforms. A few days before Christmas, another 100 veterans on their way to Fort Oglethorpe had a railroad layover in Knoxville, entertained by the local canteen service. “This fighting business is a nerve strainer,” one remarked, accurately.

Just based on the incomplete Knoxville fatality figures, there was already talk of a war memorial to cost, significantly, “at least $50,000”–and that would be over $1 million today—but there were also already sharp arguments about how best to accomplish that. Knoxville had needed a municipal auditorium for 15 years, ever since the failure of the big quonset-hut auditorium at Main and Gay. Nashville did end up building a war-memorial auditorium. Commissioner Sam Hill urged the construction of an auditorium “as nearly like the famous Pantheon on Rome as it is possible to do.”

But some thought the city also needed a dedicated tuberculosis hospital more. And beyond that, there was a philosophical argument, a very strong sentiment in favor of a memorial that was just a memorial.

A committee of local big shots, headed by White Lily flour tycoon J. Allen Smith, with assists from attorney John Webb Green, future mayor Ben Morton, and David Chapman and W.P. Davis–the last two of whom would soon be leaders of a movement to start a national park in the Smokies—Green spoke for a group of potential donors when he wrote, “we need an auditorium and we need a tuberculosis hospital, but they smack of utility.”

A proper memorial, they devoutly believed, should never be corrupted by usefulness.

They were going to build a big, notable shaft of marble or granite, as attorney John Webb Green suggested, at Circle Park, which would become known as Memorial Park. Obviously, that didn’t happen. But about 40 years later, the same John Webb Green and his wife, both elderly, led an effort on that same Circle Park to build the Frank McClung Museum, named for her long-deceased father.

Everybody weighed in. J. Will Taylor, the Republican congressman-elect, donated to the fund. W.S. Shields, who soon after that commenced the effort to establish a football field near Circle Park, favored a local-marble project, and suggested that every man, woman, and child should donate 50 cents to the memorial.

Former congressman and state Sen. John Houk thought he’d solved the controversy when, right before Christmas, he proposed that both an auditorium and a marble shaft be built, and suggested a site—what was then a vacant lot diagonally across from the Bijou. The auditorium should have statuary niches, for busts of Knoxville’s military heroes.

None of that happened. When they finally installed a World War I monument, it was almost three years later, and placed in front of Knoxville High School on Fifth Avenue—a building well known to many of the victims and veterans of the Great War.

About as deadly as the Great War among Knoxvillians was the Spanish Influenza epidemic, which peaked just two months earlier and killed almost 200 here at home. Although the viral horror was still raging in a few pockets of East Tennessee, it seemed to be over in Knoxville. One of the last to succumb was prominent Jackson Avenue wholesaler Henry Clay Bondurant, who had died at age 72 on Dec. 15.

To be sure, Kuhlman’s drugs was advertising Pure Oil of Hyomel, guaranteed to prevent influenza. It’s hard to find now.

And caroling was different. If you’ve ever encountered a caroler in the 21st century, it was probably a group of friends who came conveniently before bedtime, a week or more before Christmas, and probably only with your permission. In 1918, carolers frequently dropped in on strangers. And didn’t get started until about 11 p.m. Christmas Eve, often singing “Adeste Fideles,” “O Holy Night,” and “The First Noel” well into the wee hours. That was real caroling. Today we might call it Extreme Caroling.

One thing was especially appreciated about Christmas, 1918. After more than a year of wartime rationing of bread, sugar, butter, and cheese—all essential ingredients of an American Christmas—restrictions were dropped just a few days before Christmas, and these things became suddenly available. Christmas had never been sweeter. Kern’s Bakery, still on Market Square and a Christmas tradition for the previous half century, touted its sweets.

Exotic fruits had always been part of what made Christmas fun, but this time they had a local connection. Caswell Grapefruit and Caswell Oranges. William Caswell was a millionaire developer who lived on the edge of his favorite development, roughly what we now know as Fourth and Gill, and donor of Caswell Park, in the early days of its decades as Knoxville’s pro baseball field. At 72, he lived here, within sight of his park, but wintered in Florida, where he owned extensive citrus groves.

Here, you could get Caswell Grapefruit at T.E. Burns, the big food emporium on Market Square.

If you didn’t want to work in the kitchen, and could afford it, you could go to the Whittle Springs Hotel, which offered Christmas Dinner at noon on the 25th, and later a Dinner Dance.

Other dinners that got more attention were those for special cases. The School for the Deaf was still downtown in the big old building that’s now Lincoln Memorial University’s law school. It’s surprising that their students apparently didn’t go home for Christmas. They had a Christmas tree there, and unwrapped presents sent from home.

St. John’s Orphanage offered dinners for its 42 children. The Eastern Hospital for the Insane, at Lyons View, had a big party for its 700 inmates, including a holiday dance, when they opened presents, and a Christmas dinner.

~~~

Most issues of the newspaper featured, among the cheerful Christmas ads, an item called the Roll of Honor. It was a matter of fact report of the latest concerning the missing, the severely injured, and the dead. The lists would keep coming well into the new year.

The lists were sometimes supplemented by personal accounts arriving piecemeal, through letters from soldiers.

Many soldiers, it was observed, had little to say. One Sgt. Cobb, wounded in the upper leg, reported, “I have been through fire and torment indescribable and have witnessed many horrors.” He called this particular war, with its tanks, machine guns, and poison gas, “a scientific murder game.”

~~~

“Again the white lights winked, winked, winked all along Gay Street,” remarked a Journal reporter. “Jolly holiday shoppers jostled and joked each other in the streets; in the stores, and in the crowded trolley cars….

“Knoxville forgot the plans for a league of nations, forgot President Wilson’s visit to France, forgot the approaching municipal election, forgot the little troubles and worries that are ever present, and began an old-fashioned celebration Tuesday night.”

Because so many had shopped early, due to the wartime plea, “This year many of those on the streets and in the stores came to see and make merry rather than to shop.”

“Only one element of the old-time merrymaking was absent Tuesday night—old John Barleycorn had little part in the celebration. Outlawed by both state and nation, apparently little of the stuff that is supposed to cheer reached Knoxville this year.”

Maybe that reporter was just looking the other way. On the same page of the paper was another report: “Lid Slips Christmas Eve,” it went. “Police Kept Busy.” It went on to explain that “members of the Knoxville Police Department were kept on the run on Tuesday night making arrests on charges of drunkenness.”

~~~

It was over 20 years before Bing Crosby sang about it, people were already sentimental about the prospect of a White Christmas. It was considered possible for a while, as “cooler weather put vitality in the air, and gave the people of Knoxville a delight and a zest in their preparations.”

With all that, Christmas Day itself might have seemed another Wednesday. Some families kept an empty seat at the table, just in case there was a surprise.