Cal Johnson

Cal Johnson and History of the Cal Johnson Building on State Street

The Cal Johnson building shows the date 1898 high on its facade, and that’s a reasonable estimate of when it was built, based on its style and occupancy records. As is sometimes the case, the date inscribed may have indicated when the building was commenced, rather than when it was completed.

The Cal Johnson building shows the date 1898 high on its facade, and that’s a reasonable estimate of when it was built, based on its style and occupancy records. As is sometimes the case, the date inscribed may have indicated when the building was commenced, rather than when it was completed.

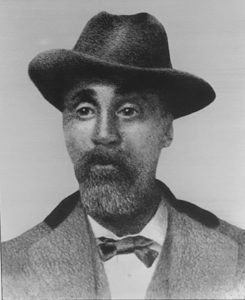

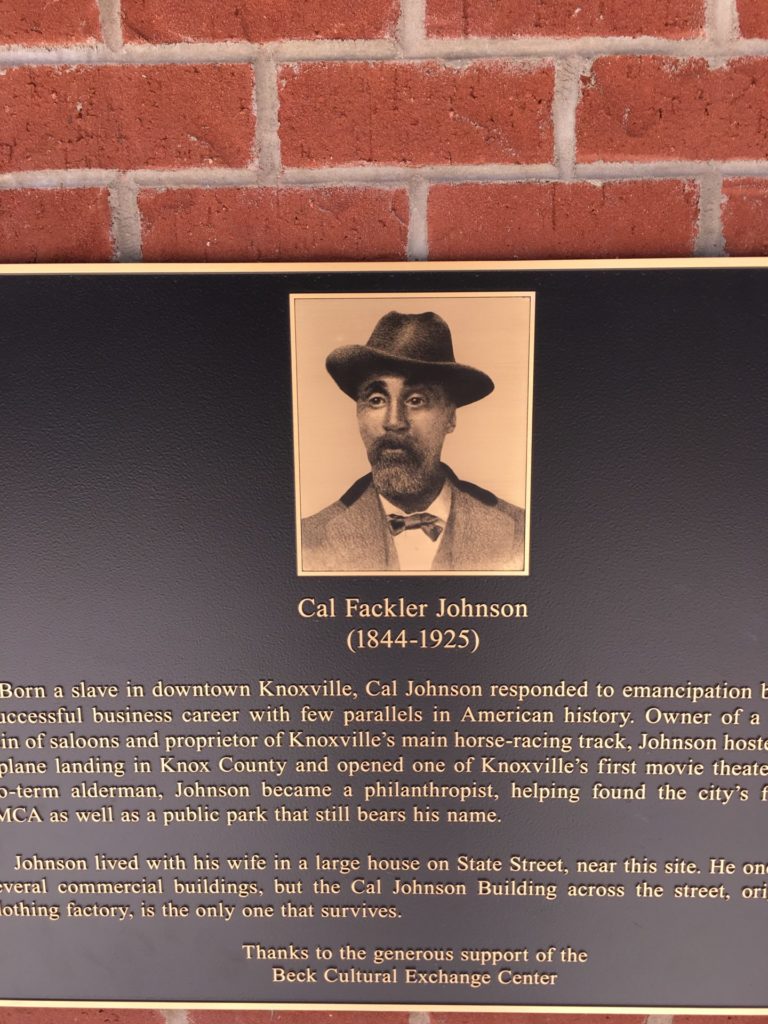

Its builder was one of the most remarkable businessmen in Knoxville’s history, with a career that may have no parallel in America. Born a slave to one of Knoxville’s oldest families, the McClungs. Cal Johnson (1844-1925) became a wealthy man.

Johnson’s father, Cupid, was well-known as an expert horseman. He died before the Civil War, but with emancipation, Cal Johnson and his older brother, John, as well as an Italian-immigrant friend, Alex Biagotti, a bond servant who had also worked for the McClung family before the war, found unusual work after the war exhuming corpses of soldiers killed on the battlefield and delivering them to the National Cemetery in Knoxville for reburial.

The Johnson brothers and their mother, Harriet, used the money to invest in real estate and business. Perhaps because it was in the vicinity of the McClung family property, land with which they were familiar, the Johnsons acquired a lot of acreage along State Street, much of it in separate parcels purchased in 1886.

This long block from Union Avenue to Commerce had an interesting heritage even before there was much architecture on it. Because of the steep declivity from Gay Street, it was difficult to build on, by the resources of the day. It was being used as a dump before the Civil War, but was occasionally cleared to host traveling circuses and other spectacles. By 1867, perhaps earlier, it was known as the “Base Ball Grounds.” East Tennessee’s first baseball games were played here in the 1860s and ’70s, when Knoxville fielded a couple of semi-pro teams, making some income based on gambling. During that period, the future site of the Cal Johnson building was probably in deep right field.

John Johnson died in early middle age, but Cal Johnson thrived as a businessman, especially known for saloons, and he owned several around town, in both predominantly black and white parts of town.

By the 1880s, he was involved in horse-racing, both as an owner and jockey, and as a sponsor of racetracks. He leased one on the south side of town (the present site of Suttree’s Landing) and in the 1890s built his own track, at the East Knoxville site now known as Speedway Circle. He entered his own horses in Chicago races associated with the 1893 World’s Fair.

He was in his mid-fifties, and well-established at the height of his horse-racing track and saloon fame when he apparently financed the construction of this new industrial building on State Street. When it was first built, it had the address of 315 State Street. Later, at some point in the mid-20th century, it was given the address of 311-313 State, perhaps more accurately reflecting its position on its block.

The site of the building was immediately next door to Johnson’s longtime residence, at 317 State Street, shared with his wife and sometimes other members of his family. The Johnson home was just a few feet south of the western end of the new building, so close that a temporary addition to the rear of the industrial building, visible in an early 20th century map, seems almost to wrap around the house.

The date 1898 is significant, because it was the year just after the most catastrophic fire in Knoxville history, which on April 8, 1897, destroyed most of the buildings just up the hill on Gay Street, on the same city block. The economy was roaring in 1898, to such an extent that most of the destroyed buildings were almost immediately rebuilt, and bigger than they had been before. This more modest building was probably being built at the same time larger buildings were going up, just across the alley on Gay Street.

This part of State was then a transitional neighborhood that it’s hard to generalize about. One block to the west, Gay Street was the location of Knoxville’s biggest, most expensive, and most familiarly public buildings. One block to the east was Central Street, then known as the Bowery, notorious for the highest concentration of saloons in the region, as well as the highest concentration of whorehouses, poolhalls, and cocaine joints. Murder was rare on Gay Street, but common on Central.

State was right in the middle, and offered a kaleidoscopic representation of all of Knoxville, and as such was one of the strangest neighborhoods in Knoxville. Among the Johnson building’s closest neighbors were the Hampden-Sidney School, Knoxville’s most prestigious private academy for white boys, and the ca. 1890 Palace Hotel, one of the city’s finest two or three hotels. However, most of the residents of State were black. And there were at least a couple of known whorehouses on the same block as the private school. Down the street were public stables. In 1904, the city would build its first fire-department headquarters on State, a stone’s throw to the north.

***

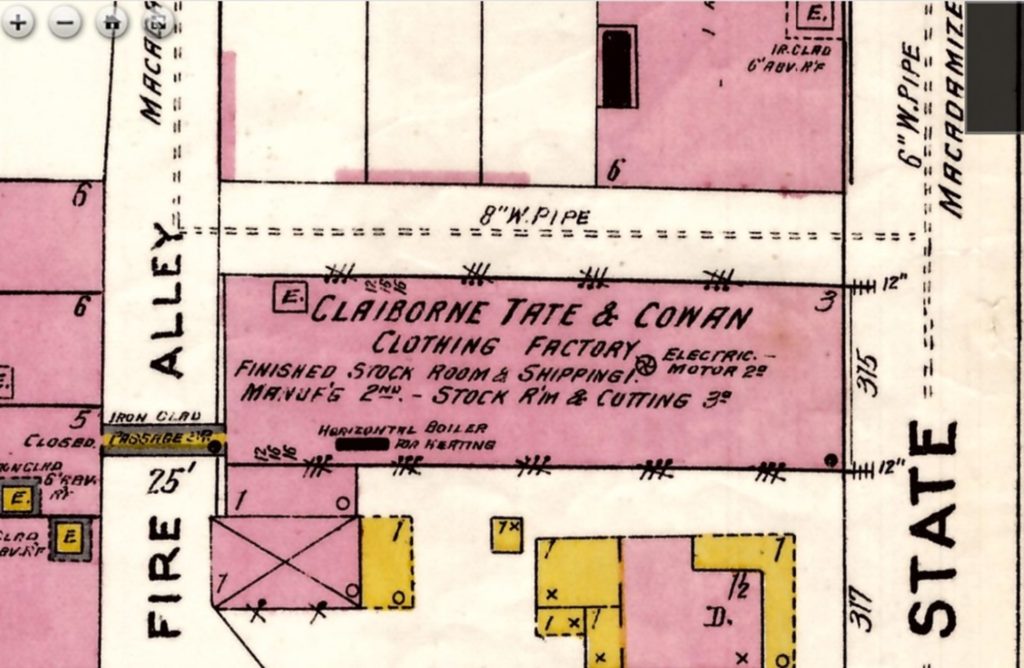

Johnson’s building at 315 State Street first appears in city directories in 1901, when it was the address of a prominent clothing manufacturer, Claiborne, Tate, and Cowan. The city directories sometime have a bit of a lag, so that business may have occupied the building in 1899 or 1900.

That first listed occupant is described in detail in a 1901 book called “Manufacturers of Knoxville” as a company as “a recent enterprise, established in 1899 by three young energetic, brainy business men. They are W.T. Claiborne, D.E. Tate, and J.H. Cowan.”

That was William T. Claiborne, David E. Tate, and James H. Cowan. The three men lived in stylish urban neighborhoods. Cowan, descended from some of Knoxville’s older families, lived at the exclusive Vendome, a tall Victorian apartment building on Clinch.

Snaborn Fire Insurance map, 1903 (detail) showing occupancy by Claiborne Tate & Cowan (University of Tennessee Libraries)

“The plant is located on State Street, near Commerce Avenue, where they manufacture men’s and boys’ suits and trousers.”

Their suit prices were not cheap, but their business was reportedly growing rapidly. “Their factory was recently overhauled and capacity increased so that they now employ from 125 to 150 people.”

Claiborne, Tate, and Cowan, which evolved into Hall-Tate Clothing, became known as one of the most successful clothing manufacturers in the Knoxville area–and spawned some retail clothing stores, like Schriver’s, founded by a Claiborne, Tate salesman.

By 1903, Claiborne, Tate & Cowan had moved to 312-314 West Jackson, a probably larger building near the Southern Railway tracks, leaving Cal Johnson’s building vacant, at least for a short time.

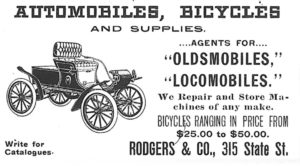

In 1904, Cowan Rodgers moved his automobile dealership into the building, after a short time in a small third-floor space on Gay Street.

Rodgers was no ordinary car dealer. Raised in an affluent Cumberland Avenue family, Rodgers was a champion tennis player and competitive bicyclist who found work in Biddles’ Bicycle Shop, on East Vine Street near Central. A few years earlier, around 1898, he began working on building automobiles. There were no large-scale American automobile producers at that time. Rodgers built at least two homemade cars, but later admitted, when he heard of the volume Henry Ford was producing, he gave up on the manufacturing side, and made his career as an auto dealer. Many years later, his company would be known as Rodgers Cadillac, but in his early days, he carried several brands, especially the “world-famous” Locomobile—the Massachusetts product that was just then converting from steam automobiles to the internal-combustion engine–and Oldsmobile, one of America’s most popular early brands.

When he occupied the Cal Johnson building, Rodgers was just 26, but his trade already covered a four-state area. He was the East Tennessee agent for Oldsmobile, and was the main source for buyers as far away as Bristol and Chattanooga.

In those days, automobile dealers didn’t always have showrooms. All those early cars were very small, basically open wagons hardly bigger than golf carts, but it’s unclear whether Rodgers used this building to show his cars inside the building. He may have simply met customers and sold them the simple cars of the day, to be delivered later. According to family lore, Rodgers worked with lists of the likely clientele for automobiles, a demographic then dominated by affluent young men, and mailed them photographs of cars he thought would interest them.

While located in this building, Rodgers performed an impressive array of barely related technical and mechanical services, carrying bicycles (the Yale and Iver Johnson makes), and doing substantial work in bicycle repair; performing electro-plating and sewing-machine repair; and another “specialty”–“constructing models of all kinds, and they have control of practically this kind of work done in the city.”

In telling his story, Rodgers allowed that his company began in 1898 as the Biddle Cycle Co. In 1904, his new building also hosted the Biddle Machine Shop, John C. Biddle, proprietor. (Biddle had employed Rodgers at his earlier bicycle and machine shop on East Vine, and there, ca. 1898-99, Rodgers had built the first automobiles seen in Knoxville.)

Rodgers moved to 710 South Gay Street in 1906, a much more conspicuous location, across the street from the newspaper offices, near some of the new movie theaters, and hardly a block from Staub’s Theatre. He later moved to Henley Street at Gay, where his showroom was well known for many years. By the 1930s, Rodgers was already boasting of being the oldest car dealership in the South. Automobiles were just catching on. If one person could be said to have introduced automobiles to Knoxville, and promoted them as a practical purchase, it was Cowan Rodgers.

The Rodgers family apparently considered the 315 State address to be especially significant in Rodgers’ evolution, because it was the only one of his four early business addresses mentioned in a short 1969 News-Sentinel retrospective on the background of “the Oldest Dealer in the Southland.”

***

After Rodgers left in 1906, the Cal Johnson Building almost immediately found use again as a clothing factory. The Regal Manufacturing Co., led by a G.L. Price, about whom little is obvious, and secretary-treasurer Samuel D. Coykendall, described as “pants manufacturers.” Eventually with Price out and Coykendall as president, Regal would remain for about three years. In 1909, Regal moved to 316-318 West Jackson—right next door to the Claiborne, Tate building.

By the time it was 10 years old, the Cal Johnson building should have had a reputation as an incubator for businesses that grew too large to fit in it. It would appear successful in that role, because most of the early businesses located in this building did thrive and grow, even if they reached full flower elsewhere.

The building is listed as “vacant” in 1909 and 1910.

In 1911, clothing manufacturers Suttle & Beeler—run by Harry H. Suttle and Ulysses D. Beeler–occupied the building, and while here also developed an address just around the corner at 208 Commerce Street. This may have been the first time those two buildings, cross-alley neighbors, were associated. The family of Ulysses D. Beeler was socially prominent, and lived on Gay Street, when only a few affluent families lived there. He was soon to be the father of Betsey, later to be known as the popular Knoxville historian and author Betsey Beeler Creekmore, who also co-founded the Dogwood Arts Festival.

By 1912, though, Beeler and Co. had left, and it was the Knoxville Overall Company, run by John Bowman, who lived on Temple Avenue, near the university. His secretary-treasurer, Eugene Bowman, lived at the same address. Here they manufactured overalls, but also some other garments, as the motto “overall — shirts — pants” indicates. Knoxville Overall remained through the World War I era.

The Bowmans moved their operation, now renamed Bowman Overall, less than a block to the south, at 401-405 State. By 1922, Bowman claimed to be producing 3,000 pairs of denim overalls per day, and had the contract to supply the hundreds of employees at the Southern Railway’s huge Coster Shops rail-car plant.

In 1919, the building is again listed as “vacant.” But the following year, the Reliance Overall Co. occupied the building, with the Coykendall family in charge: Samuel Coykendall, president—he had been associated with the building more than a decade earlier, and apparently trusted it–J.B. Coykendall, vice president, and Edward Coykendall, secretary-treasurer. J.B. Coykendall, in particular, would become a wealthy and prominent Knoxvillian in years to come.

Reliance remained until 1922, when the building underwent a shift. The Cal Johnson building became home for two or three years to the Cherokee Motor Company. The building’s second era as an automobile dealer came 20 years after its first.

The 1920s was a very different era for automobiles, when they were no longer noisy toys for youthful daredevils, but more substantial luxuries or even necessities, practical and fashionable transportation for affluent families, in an era when, for the first time, investors were developing neighborhoods that were beyond the streetcar grid and hard to reach without an automobile.

Here, Cherokee carried mostly Studebakers. The Indiana-based manufacturer was famous for an expanding array of models, notably the stylish “Big Six” (cylinders, that is) touring car, advertised as so graceful, fashionable, and easy to drive that even women liked them.

Cherokee did well here. In fact, in June, 1923, Cherokee got a prize for selling the most Studebakers per capita in their market in the nation. To sell their cars, Cherokee was known to accept “trade for real estate or anything of value.”

Cherokee’s choice of location is interesting. For much of the 20th century, car dealerships tended to cluster near train or bus stations, as if to tempt passengers to step up to a more luxurious mode of travel. Knoxville’s first inter-city bus station was on State Street at the corner of Union, and the larger Union Bus Terminal was built around 1930 between State and Gay Streets, very near 315 State.

It’s likely that many older customers remembered Cowan Rodgers’ early venture here, too, and the association with a groundbreaking car dealership didn’t hurt.

The president of Cherokee Motor Co. was Claude Reeder, whose family would be prominent in Knoxville automobile sales for decades to come.

Cal Johnson Building owned by Cherokee Motor Co., circa 1930s. The front porch of Cal Johnson’s former home can be seen immediately to the left of the building. (McClung Historical Collection.)

It seems likely that Cherokee was responsible for cutting the garage bay doors into the building’s facade. However, when Cherokee occupied the building, they were already planning for something bigger and newer at their previous location across the street. It was to be a new, modern automobile emporium, a broad four-story garage with show rooms for both new and used Studebakers. They heralded their car palace in a grand opening with live music, free cigars, flowers, and iced lemonade, on Monday, June 16, 1924. Hundreds attended the festivities, which went until 10 p.m.

Although most of Knoxville’s automobile dealers were coalescing on North Gay Street, Reeder remained on this block of State Street into the late 1960s, when the family moved their Chevrolet dealership out west, to Kingston Pike. That 1924 building was torn down.

But Cherokee’s wheeled advertisement on the facade of the Cal Johnson building, painted early in the Coolidge administration, remains discernible even into the 21st century.

***

As an old man, Cal Johnson became known to both races as a friendly presence on State Street. He had a green lawn, and often sat on his broad front porch, calling out to friends and strangers alike, tipping his hat, inviting them to come up and sit with him, even occasionally to share a meal.

Cal Johnson fell ill in the late winter of early 1925, and the newspapers followed his health closely, as doctors examined him at his home at 307 State Street, next door to the industrial building he’d built more than a quarter-century before. On April 7, he died there, at age 81.

The News-Sentinel described him as the “wealthy Negro philanthropist, who made a fortune in race horses and spent much of it to give parks and other facilities to his people.” It remarked that he was born a slave but died one of the wealthiest black men in Tennessee. “He was born at the present site of the Farragut Hotel and died within two blocks of that spot.”

Knoxville’s leading white citizens were among his pallbearers, including Capt. William Rule, Union veteran, longtime newspaper editor, author, and former mayor.

His wife, Maggie, who was involved in a legal challenge from other more distant relatives for Johnson’s fortune, died of cancer soon afterward. It’s not clear whether they still owned the industrial building with Johnson’s name on the facade, but it was not one of the four properties under dispute in the inheritance case.

Reporters found it poignant that the sidewalk tree for which his classic old Lone Tree Saloon had been named died not long after Johnson did.

His State Street home was used for sales of Auburn-brand automobile in the late 1920s. The house with the welcoming porch was torn down probably not long after that.

***

Johnson’s death came just as the tenants of his building were in transition. That year, the Deaver Dry Goods Co., which had its main entrance at 200-202 Commerce, began using the Cal Johnson building as a garage and storehouse.

From that moment on, the building at 315 State Street would no longer be the main address of a business, but would serve as a utility building or warehouse for businesses in buildings facing Commerce.

Deaver Dry Goods building, 1930s,. Cal John son Building on the left. (McClung Historical Collection)

Joshua L. Deaver lived on Melrose Place, Ernest L. Deaver on Overton Park. Their wholesale company, which dealt in a variety of goods, had recently combined with a rival, Farris-Herd-Crenshaw Co. They announced that they aspired to be “one of the largest wholesale Dry Goods, Notions, and Furnishing Houses in the entire South, adding new lines of merchandise and affording unusual facilities for serving the Retail Merchant.”

A small news item in late September, 1929, describes a car fire inside the building. It was a minor fire, damaging only some rugs before it was extinguished, but the news report tells us that Deaver used the building partly as a garage, and also stored rugs there.

At times, at least, Deaver’s was open to the public, which the company invited to visit the store in big advertisements in the paper. It appears that the main attraction was in the buildings fronting Commerce, though.

In the late 1950s, the Cal Johnson Building’s address seems to have shifted slightly from 313-315 State Street to 311-313 State, perhaps reflecting adjusted city street measurements.

Deaver turned out to be the longest user of the building, a total of about 47 years. It was still being listed as Deaver’s warehouse as late as 1972. After that, the building, was listed as “vacant” for several years.

Deaver closed by that name around 1973, though some of its executive staff remained at William R. Moore, which occupied Deaver’s old headquarters at 200-202 Commerce for much of the 1970s, before moving to Baum Drive in Bearden.

The use of the Cal Johnson building after that would seem elusive, based on library records alone, which don’t associate the address with any business after Deaver left it. By 1980, the building’s address is no longer listed at all, as if it’s no longer there. That’s unusual, especially for a downtown building.

However, we know that Bacon & Co., acquired the building during this period and used it for storage. It was a longtime neighbor. Founded by John A. Bacon, the company first advertised itself as a “mill agent” in the early 1930s and moved its headquarters next door to Deaver around 1934, at 206 Commerce. Bacon eventually occupied Deaver and Moore’s Commerce Street headquarters address. It’s possible that the Cal Johnson building, which stood behind those buildings, was by then considered part of the Commerce Street plant, and was therefore no longer listed as a building with an address of its own.

Cal Johnson’s Lone Tree Saloon on the 200 block of Gay Street, circa 1920s (Courtesy of Knox Heritage)

Meanwhile, all the other known buildings ever associated with Cal Johnson have vanished over the years. The building most famously associated with Johnson in his lifetime, the one on the 200 block of Gay Street that once hosted the Lone Tree Saloon, was torn down around 1980 to make way for a surface parking lot. His other buildings along Central, including saloons and one movie theater, have also been lost. In the 1920s, soon after his death, his East Knoxville racetrack was redeveloped as a residential neighborhood.

The building survives as the only architectural relic of Johnson’s extraordinary career. The 21st century revival of interest in African-American history has been a context for much new interest in the life of Cal Johnson. In 2017, the new development called Marble Alley unveiled a plaque in Johnson’s honor, across the street from his last remaining building.

Jack Neely, May 8, 2018

Special thanks to Daniel Odle for funding the research for this story.