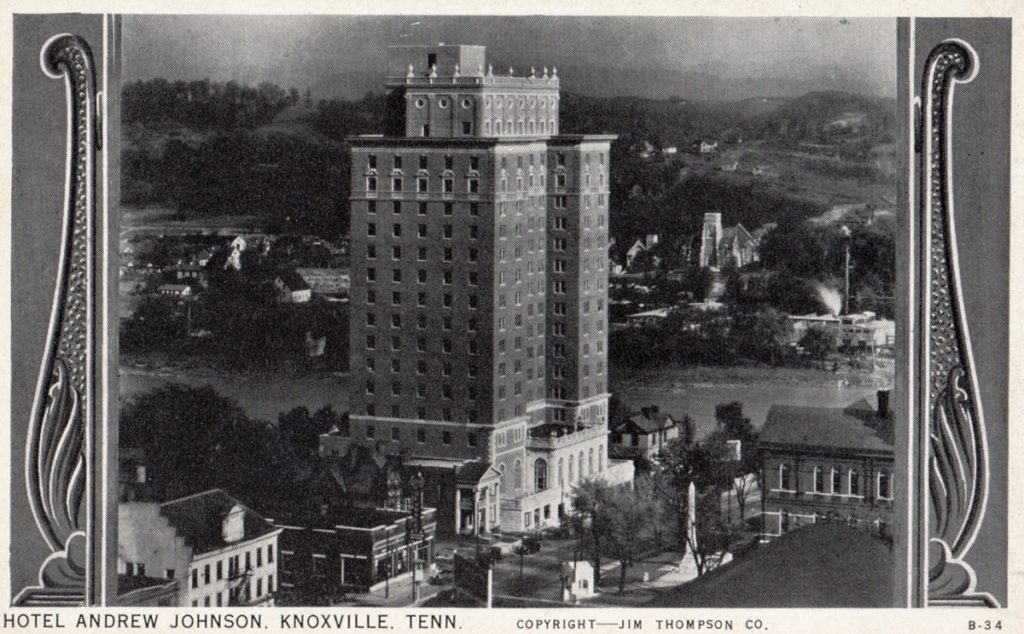

Andrew Johnson Hotel

Gay Street’s Wallflower: The Andrew Johnson Hotel by Jack Neely

It has a story unlike that of any other building in the world. The Andrew Johnson is the long-sought missing link between Hank Williams, Amelia Earhart, and Jean-Paul Sartre.

It was built in the 1920s by investors looking toward the expected tsunami of tourists headed for the brand-new, in fact not quite completed project known as the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Knoxville itself seemed to call for a new hotel every few years, anyway. The Farragut, at Gay and Clinch, was almost a decade old. The big Atkin, near the train station, was a decade older still. A great skyscraper of a hotel near the river seemed just the thing.

It was originally to be called the Tennessee Terrace, which would have been a good name. However, there was another idea in the air. Andrew Johnson was the bizarre sideshow attraction of American politics, the duckbill platypus of the Civil War era, who drew sharp criticism from both sides even in Knoxville, and at least once even gunfire, as he ducked an assassination attempt on Gay Street. He tried to make up with ex-Confederates in the years after the war by doing what he could to damp civil rights and revive white supremacy. He was the last of Tennessee’s three presidents, though he was never elected to the office, and was for better or worse not an effective one—and he was the first to be impeached.

No one would have named a big building for Andrew Johnson in the years just after the war, nor at the time of his death in 1875, nor for decades after, when historical assessments of him were negative. However, your reputation can keep changing, even 50 years after you die. By the 1920s, after the release of some documents that made Johnson sound at least occasionally brave and steadfast, the poor small-town tailor who became president was seen as a self-made American hero.

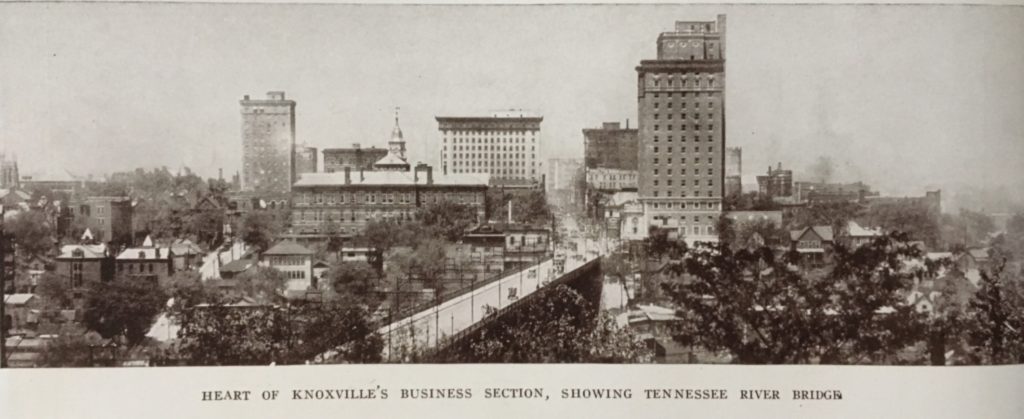

Downtown Knoxville, 1920s, looking across the Gay Street Bridge towards the Andrew Johnson Hotel on the right. Courtesy Paul James.

In the late 1920s, developers were persuaded to drop the generic-sounding Tennessee Terrace to rename the project the Andrew Johnson Hotel. Designed by Baumann & Baumann, it would be the world’s biggest honor to the 17th president, and for almost half a century the tallest building in East Tennessee.

An amazing assortment of people came through the doors at 912 South Gay St. over the years. In 1932, it hosted a banquet of coaches and administrators toasting the formation of the brand-new Southeastern Conference, hours after its founding.

Maynard Baird’s Southland Serenaders, also known as Southern Serenaders, Knoxville’s most widely renowned jazz dance band. Courtesy Tennessee Archive of Moving Image and Sound.

Its early music was jazz. Upon its opening, Maynard Baird’s Southern Serenaders, an early dance orchestra, played on the roof, with loudspeakers that allowed the music to be danceable as far away as Market Square. In 1935, it was briefly home to WNOX’s Mid-Day Merry-Go-Round, the live radio show that launched many radio and recording careers. Roy Acuff, not yet well known in Nashville, was a regular in those days. After rowdy fans posed a daily problem crowding the elevators, management asked them to leave.

Annemarie Schwarzenbach

Amelia Earhart showed up in 1936, driving alone through the mountains. When reporters discovered her, she reluctantly agreed to an interview as she ate in her hotel room. She remarked then that she did not expect to live to see old age. She vanished the following year. Swiss novelist and journalist Annemarie Schwarzenbach stayed at the hotel a few months later, and wrote about Knoxville’s economically stratified society for a European audience.

In 1943, Russian composer-pianist Sergei Rachmaninoff, suffering from undiagnosed cancer, spent a painful night at the hotel after what would be remembered as the final performance of his career. It was the same night that the hotel played a role in a regional premiere of the 1943 movie Tennessee Johnson, starring Van Heflin as a rare heroic version of the president in his rise to power. The patriotic wartime movie opened at the Tennessee, and afterward was celebrated with a ball at the Andrew Johnson Hotel, attended by members of Johnson’s family, including the president’s granddaughter. It must have puzzled Rachmaninoff.

In early 1945, French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre checked into the Andrew Johnson, on a press junket to report on the U.S. war effort. But during his several days at the Andrew Johnson, he wrote an essay about American cities that was published in Le Figaro, and later in a book.

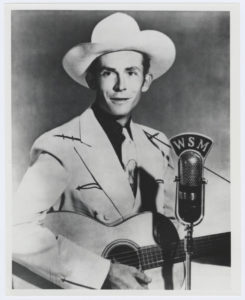

Hank Williams. Courtesy Wilson Library, UNC.

And, of course, on the last night of 1952, 29-year-old Alabama songwriter Hank Williams, ostensibly on his way to shows in West Virginia and Ohio, stopped in at the Andrew Johnson for a shot of morphine and reportedly some liquor, to enjoy the last night of his life. Whether he died in the hotel, or soon after, in the car, depends on which contradictory account you credit. We can’t know whether he was aware that he spent his last hours in the same building where his idol, Roy Acuff, had begun his career about 17 years earlier.

Playwright Tennessee Williams stayed at the Andrew Johnson for a few days in 1957 when he came to Knoxville to attend his father’s funeral and burial. King Hussein of Jordan attended a reception there in the early 1960s. Actor Tony Perkins stayed there when he came to town for the premiere of The Fool Killer in 1965.

Duke Ellington stayed there a couple of years later, and gave an interview in the restaurant. There are other stories, of legendary photographer Margaret Bourke-White, who was allegedly locked in her darkroom, trapped for some hours in a windowless room in the Andrew Johnson in the ’50s, that are harder to nail down. Some people lived there.

Postscript: For details on the hotel’s redevelopment from Knox County School’s headquarters to a multi-use hotel, retail, and residential building, visit Inside of Knoxville’s blog post on it with links to related stories.