Anderson, Harris, and Wade: Suffrage’s Forgotten Local Champions

By Jack Neely

By now we all know the story of Rep. Harry T. Burn, the representative from Niota who changed his mind on women’s suffrage and enabled the 19th Amendment, which guaranteed women the right to vote. Google his name, and you’ll find 30 different versions of his familiar story of the nudge from his mother and his wobbly vote tilted the state, and therefore the entire nation, to approving the vote for all American women. It all happened one dramatic day in Nashville, in August, 1920. It’s worth telling, one of the most dramatic stories in the constitutional history of the United States.

He was once portrayed in a major motion picture, Iron Jawed Angels, with Hillary Swank. Recently he’s been the subject of a musical play and a clever music video. There’s a bronze statue of Burn and his mother, Febb, at the corner of Clinch and Market. But Harry Burn was from McMinn County. What about Knoxville’s representatives in the room? Did they show up that day?

Yes, they were there, too. Knoxville’s delegation consisted of three representatives who were present in that big, noisy room, all of them Republicans.

Their votes each counted just as much as Harry Burns’ did. Maybe because the lobbyists and pundits were better at predicting how they would vote before the roll call, they’re obscure in history. I’ve never seen any of their names in a book or recent article. In fact, unless you’ve studied this subject specifically, using sources not published in articles and books, you’ve probably never heard of any of them.

They were three very different fellows. All of them were recent newcomers to the House, which is not to say they were spring chickens.

Truth be told, one was not exactly a true freshman, because he’d had a desk in Nashville many years earlier. By far the most colorful of the three, Joseph Cowan Harris was a Maryville College alum. Politics was a tradition in his family. Back in the 1870s, his dad had been a county “squire,” an elected magistrate; his older brother was once a two-term Knoxville alderman.

About 70 at the time of the vote, Joe Harris was an auctioneer and real-estate speculator, known for buying and selling farms. He’d been around a long time, and people recognized his name even deep in the Victorian era. The first time he’d been elected to the legislature was back in the 1880s, when “Our Bob” Taylor was governor. The Suffrage fight became known as the War of the Roses, but it was not the first Tennessee political fight that earned that designation. The original “War of the Roses,” was the gubernatorial election that pitted the Taylor brothers, Bob and Alf, representing two political parties, against each other. To demonstrate that he was not in the pocket of any special interest, in 1887 Harris had been quoted, “I don’t give a damn for anybody except the ladies.” He eventually married one named Mary Richardson.

A man of wide interests, he was a published poet. Though sometimes described as a “humorist,” Harris delivered a multi-stanza eulogy for General Sheridan to a reunion of both Union and Confederate veterans in Chattanooga in 1889. He had sojourned in the Wild West on a real-estate adventure.

In 1912, Harris had leaked that he had become a “multi-millionaire” thanks to an inheritance from an obscure British source.

About the Suffrage issue, Harris was coy about commitment, but by early summer, most guessed he was pro, and he affirmed his pro-suffrage sympathies before the vote.

***

Joe E. Wade was a much younger man than Harris, but not so colorful. He was about 39, a career plumbing inspector, a job he’d had since 1911. It’s what he did before, during, and after his historic vote. He lived with his wife and two daughters lived in a modest house near the train tracks on the western fringe of old North Knoxville.

It’s unusual for plumbing inspectors to run for state legislature, but Wade was an earnest-looking guy who had a leader’s profile. “Help me and you will have nothing to regret,” went his introduction in his open letter to the Citizens of Knox County. “My motto is ‘Do Right.'”

He had some distractions in 1920, facing charges of inefficiency on his job. They would eventually be proven groundless, and he kept his job for years to come, but that summer the complaints may have weighed heavier on his mind than his place in constitutional history.

He was not a guy who enjoyed his uncertainty making him the center of attention. He didn’t flirt. Suffrage apparently passed his “Do Right” test, and he openly supported suffrage. He was downtown every day, and maybe he was persuaded by one or two of Lizzie Crozier French’s public speeches. In any case, people knew how Wade was going to vote before he got to Nashville.

By committing to the cause early, Wade assured that his name would stay out of the papers–and that, for better or worse, he would never be famous.

***

Kendall Anderson was a vote they weren’t quite as sure about. A prominent attorney of 53 at the time of the vote, he was, like Harris, a Maryville College alum. He’d married a Georgia woman named Evelyn, a career journalist who wrote for several papers, and eventually became a staffer at the News-Sentinel. His name had been circulating as a political contender since the 1890s. Maybe because he and Evelyn had seven kids, he gravitated toward education, and ran for the school board.

Known to friends as Ken, he practiced both family and criminal law. He joined the prominent firm of Shields, Cates, and Mountcastle–its founding partner was then U.S. Senator John K. Shields–and after 1913, Anderson had a roomy office in the big new marble monument known as the Holston Building. As he got older, he developed a lean, rugged look, that some might call Lincolnesque.

He was one of the school board’s more outspoken members, notable for his push to bring county schools in newly annexed South Knoxville into the city-schools fold. It was a subject close to home, because he and his large family lived in South Knoxville. In 1920 he was also agitating for better salaries for teachers.

Soon after they were elected, all three–Harris, Wade, and Anderson–a proposal for a new constitutional amendment greeted them in Nashville. It wasn’t one about suffrage. It was about prohibition. All three signed a pledge supporting the Eighteenth Amendment. It was a popular stand in 1919, even among some drinkers. Of course, by then Knoxville had been dry for just over 11 years, so a new federal law wasn’t going to make any difference here. It was a matter of just forcing the rest of the nation to join the misery.

Many legislators serve long careers without ever seeing a constitutional amendment come before them, but this class of legislators, in one term, had already passed one, and at a dramatic moment. Tennessee passed the Eighteenth Amendment on Jan. 13; it passed nationally when Nebraska okayed it three days later.

So it was an unusually seasoned legislature of proven Constitution changers that faced the next challenge the Nineteenth amendment. It may seem odd today that allowing women to vote was not nearly as popular, nationally, as banning alcoholic beverages had been.

Rep. Anderson had supported a decision the previous year to allow Tennessee women to vote in municipal and presidential elections; it’s often forgotten that women here did vote in local elections in 1919. But as of the end of June, he was still “noncommital” about the 19th amendment, which would enable women in every state to vote in every election. Anderson’s neutrality made him briefly a national celebrity, mentioned in papers from California to Massachusetts, as he became a target for those who thought they could persuade him to be the one who would tip the scales nationally. By summer, everybody in America knew the Tennessee legislature was going to make the difference, the elusive 36th state. And the decision, in the closely split legislature, would be in the hands of the very few who hadn’t yet announced their commitments.

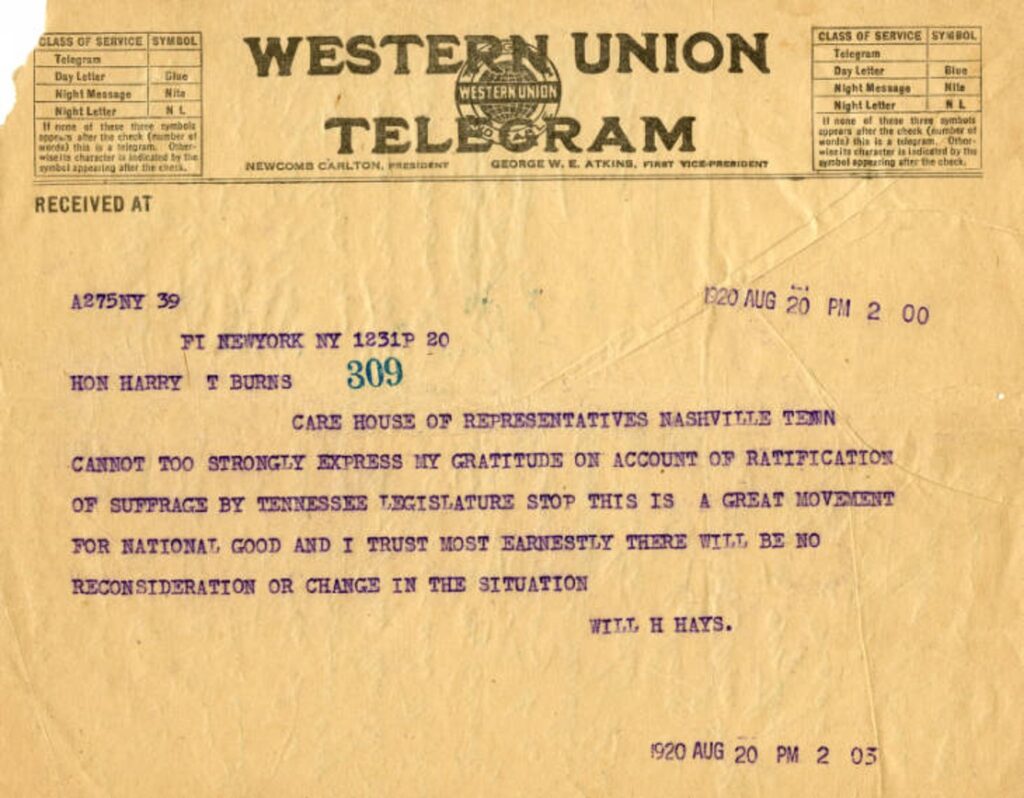

The national Republican Party was split on the issue, but its leadership, in consultation with presidential nominee Warren G. Harding, wanted to get in front of the parade, and make suffrage a Republican victory. On Aug. 11, Harris and Anderson–along with young Harry T. Burn–were among 11 legislators personally targeted by Will H. Hays, chairman of the Republican National Committee, with an urgent pro-Suffrage plea. (Many years later, Hays would be known for Hollywood’s censorious Hays Code. In 1920, he was progressive-ish.)

Telegram from Will H. Hays to Harry Burn supporting the passage of the 19th Amendment, August 20, 1920 (Harry T. Burn Papers, McClung Historical Collection)

Although he was sometimes considered pro-suffrage, Anderson kept everybody guessing. A week before the vote, a report claimed “Rep. W.K. Anderson is in doubt, and is not counted upon as an assured supporter, but suffragists have reason to hope to find his name in their column…”

At some point in the next few days, Anderson let it slip that he would vote pro. The critical showdown came on Aug. 18.

In the interest of inclusion, there was a fourth local character in the drama, Rep. J.E. Cassady–apparently not well known to reporters who sometimes referred to him as E.H. Cassady. He’s not usually counted as part of the Knoxville delegation, because he lived in Loudon, though his “floterial” district covered parts of rural West Knox County.

The socially conservative attorney had, a few months earlier, supported a ban on showing movies on Sundays, and his reasoning was so eloquent, it almost makes you want to revive it. “I’m from back in the country,” Cassady said, “where the country music of the night is the hoot of the owl and the song of the whippoorwill, with occasionally a croak from the tree frog and the cackle of the katydid, the low of the cow, and the bark of the dog.” Movies shouldn’t even try to compete, he said, especially on the Sabbath.

But it was said Cassady was interested in the Suffrage issue, but he revealed that certain anti-Suffrage women in Nashville were threatening that he would face “political disaster” if he voted Aye.

Harry Burn was at the fulcrum that day, the center of the drama, most pivotal when he broke a 48-48 deadlock, declining a motion to table the vote. When the amendment itself came to the floor, the first to shout “Aye” in the alphabetical roll-call vote was W.K. Anderson of Knoxville. With his vote and 49 others–including those of Burn, Harris, and Wade–the Nineteenth Amendment passed with the bare minimum to make a majority in a 99-seat legislature.

Because Tennessee was the 36th state to pass it, constituting three-fourths of America, it became national law.

Some local newspapermen at the time brought out one curiosity. Knoxville’s Anderson was the first to vote Aye. The last, and the one who put it over the top, was Knoxville’s Joe E. Wade. So due to an alphabetical accident, Knoxvillians began and ended the vote that gave the Nineteenth Amendment to the nation.

***

In Nashville’s state house they registered their votes to change America. Then, before summer was over, they went home. Lizzie Crozier French herself co-hosted a Knoxville fete in honor of Anderson, Harris, and Wade, that September. Of course, young Harry Burn was the featured speaker. Then the pro-suffrage trio from Knoxville pretty promptly vanished from history, even local history.

Knoxville suffragists’ Victory banquet at Knoxville’s Lyceum, hosted by Lizzie Crozier French herself, honored the local legislators, including Anderson, Harris, and Wade, who had voted for suffrage weeks before. The featured attraction was speaker Harry T. Burn, but there were about 20 other speakers, from female suffragists to male politicians who had helped pass the Nineteenth Amendment. The banner on the wall honors suffragists of the past, including Susan B. Anthony, Frances Willard, and Tennessee’s Elizabeth Lyle Saxon, who didn’t live to see it happen. (McClung Historical Collection)

Floterial Rep. J.E. Cassady was the only one associated with Knox County who voted no. He cited an obscure constitutional principal, concerns that women would have to serve as soldiers, and some esoteric math that suggested doubling the power of city voters would somehow result in less representation for country folks. “Being from the country as I am, I shall stand with the country people,” he declared, as he declined to run for re-election.

The three Ayes remained in the public eye, as public servants, or contenders in a variety of political races, sometimes successfully, sometimes, not. But after 1920, their roles in passing the Nineteenth Amendment were rarely if ever mentioned. When their names came up, it was always about other controversies, the City Charter, conflicts of interest, new taxes, new schools.

***

The eldest of them, Joe Harris, remained characteristically unpredictable. Perhaps restless in the Republican Party, a very different Republican Party from the one he knew in his youth, Harris ran as an independent in 1920, just after the famous suffrage vote, but withdrew before the election. Well into his 70s, he ran as a Republican in 1922, 1924 and 1926, but never got the nomination. After the last disappointment, he left his home town, and settled in Somerset, Ky., where he died at age 85 in late 1934.

***

Probably the strongest Suffrage supporter in Knoxville’s delegation, Joe E. Wade was re-elected to the legislature in 1922, despite some public controversy. It was not over his Suffrage vote, but had to do with conflict of interest, and his roles straddling city and state realms: he was working for city government while serving as a representative in state government.

Although he was the youngest of Knoxville’s three suffrage supporters, he was the first to die. About five and a half years after the vote, he was just 45 when he succumbed to pneumonia at the apartment he shared with his wife and daughters in the Elliott on Clinch Avenue.

There was a hubbub about who would be his replacement as plumbing inspector, but beyond that Wade’s name was rarely ever mentioned in print again.

***

W.K. Anderson returned to his role as treasurer of the Board of Education, and his concerns about Knoxville city schools, now pushing to build new school buildings and improve old ones. He was a familiar and important figure in 1920s Knoxville, but his fate shows how quickly we forget.

He ran for Register of Deeds for Knox County in 1922, in a crowded field of nine contenders, one of which, notably, was named Edith Rutherford. They both got a lot of votes, but lost in a messy Republican primary that generated charges of overt fraud, even vote-buying at the polls. Anderson’s wife, Evelyn, was especially vocal about the alleged fraud, declaring “whiskey was one of the influential factors in determining the result” and that poll supervisors were almost openly distributing cash to voters.

Meanwhile, most of the Andersons’ once-large South Knoxville family had grown up and drifted away. One son, a professional jockey, had been killed in a Tijuana horse accident in 1923. Three of his children had moved to California, one to Columbia, S.C., two to Louisville, Ky.

Then, in 1926, he and the now-elderly Joe Harris both vied for the Republican nomination for the House. Anderson was the one who made it back. Maybe it was the embarrassment of losing to his old colleague that hastened Harris into retirement in Kentucky.

But toward the end of his first term back, the Andersons suffered some bad luck. During the holidays in early 1928, Evelyn was severely injured when her dress caught on fire in the kitchen.

Anderson was re-elected that year, but early in that third term, in 1929, he suffered a stroke in Nashville. Hardly any action he ever took as a politician drew as much press as his medical condition. Was he dying, or was he recovering? As is often the case, the answer was not necessarily.

He was out of work for months. In a trustee’s sale at the courthouse later that year–the same month as the stock-market crash, in fact–their house and some other real estate in South Knoxville was sold to satisfy their debts.

After convalescing at his daughter’s home in Louisville, Anderson attempted a return to the legislature and to the Knoxville

State Capitol, Nashville, circa 1901 (Library of Congress)

courts as a defense attorney, and to the legislature, but not for long. Injured in a fall working on a criminal case at Brushy Mountain Prison, his fortunes seemed to slide only further. He and his wife found a place to live somewhere in the countryside near Fountain City.

In 1932, he told a newspaper he might run for the legislature again. “I figure I can lay around in Nashville just as well as I can lay around here.” He jumped at opportunities for grim humor where he could find them. Though listed as a candidate, he was not nominated.

The fact was he had become a patient under the care of various family members. In 1934, he was found to be living with a family near the jailhouse, “broken by disease and without funds.” There’s no mention of Evelyn in many of the later items about Anderson; it’s not clear they were always together.

The Knoxville Sentinel Building on Gay Street at W. Church Avenue, 1920 (McClung Historical Collection)

The News-Sentinel remarked, “W. Ken Anderson, once a member of a leading Knoxville law firm, formerly a member of the City School Board, several times Knox County legislator, but now afflicted and destitute, plans to leave Knoxville.” His daughter up in Louisville took him in again. He also stayed with two of his sons.

But it appears none of his children were able to deal with an old, infirm man for long. By 1937 he was back, living at the Maloney Home for the elderly. The county housing was located at Maloneyville, the penal farm, it was sometimes known as the “Poor Asylum.” He was reportedly looking forward to benefiting from the new thing called Social Security.

A reporter writing about the home’s inmates and the prospect of Social Security didn’t recognize this old man as a former legislator. “Mr. Anderson says he’s a lawyer…” The phrasing gave the perhaps skeptical reporter deniability, just in case the weird old man was making it up.

The old inmate was perhaps too modest to mention that there was a moment, back in the summer of ’20, when his name had appeared in dozens of newspapers across the country, when activists as far away as California wanted his attention, because he was one of the last uncommitted votes for Suffrage.

His wife, Evelyn, died in May of the following year; Former Rep. WK “Ken” Anderson died five months later. His obituary did remind us that he had been a state legislator, at some vague time in the past–but not that he had once played a critical role in passing a critical amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

***

In fact none of the legislators’ obituaries included any mention of that day the eyes of the nation were on them, back in ’20.

There’s an awkward period in the memory of both people and events, when they’re too long ago to seem current and relevant but not long enough ago to seem “historic,” or even particularly interesting. It made a difference–Knoxville was even voting women into public office as early as 1924. Still, I get the impression that for a generation or so, the suffrage issue was considered yesterday’s news, something accomplished by funny old women in old-fashioned clothes and hats and big hairdos.

Harry T. Burn outlived Knoxville’s Anderson, Harris, and Wade by almost 40 years. He even lived long enough to see suffrage return to public conversation as a subject of historical interest. By the 1950s, he was regarded with some respect, if not awe, making speeches on the subject at the East Tennessee Historical Society, back when it met at the old Lawson McGhee Library just north of Market Square, about his historic Suffrage vote. He was not only the vote that tipped the scales, but by then he was one of the few survivors of that dramatic legislature. In 1970, when Georgia Gov. Lester Maddox held a ceremony symbolically approving the amendment–Georgia rejected it in 1919–he invited Burn to be a guest of honor. Burn is the one with the Wikipedia entry today.

Still. If not for each forgotten member of the Knoxville delegation, we would never have heard his name, and he’d certainly have no statue in downtown Knoxville, across the street from Anderson’s old office.

At the funerals of each of Tennessee’s pro voters, mourners could have quoted a poem auctioneer, and occasional representative Joe Harris had written about Sheridan back in ’89:

“And though his days on Earth are done,

His fame, his deeds are ours…”