An Elegy to the Strip

Is West Cumberland Still the Cultural Icon of Our Youth?

Recently the western blocks of Cumberland Avenue have become the subject of much mourning, and it’s not hard to understand why. What was once a lively and unpredictable corridor of distinctive cafes and delis and offbeat shops and live-music clubs, most of them in historic-looking brick buildings, is becoming a clean canyon of glass and steel. And in the change, we’re losing some business institutions, including the two oldest restaurants in the whole central-Knoxville area.

The changes seem sudden and almost violent; they also may be deceptive.

There’s some irony in the transformation, and in the reaction to it. The enormous architecture we see today came deliberately, after lots of study and public meetings, largely in response to the perceived decline of the Strip, and a bold city plan to revive it.

Many of a certain age loved this stretch that became known as the Strip during the counterculture era. It thrived as a restaurant and nightclub district from the 1960s through the 1980s. But in the 1990s, as buildings that once held multiple bars and shops were demolished for parking lots for banks and fast-food chains, Knoxville’s least-predictable address began to resemble any interstate exit in America. By 2000 or so, former patrons were complaining that the old Strip had become a wasteland of parking lots for businesses that came and went. “There’s no there there,” one neighboring architect remarked in 2010 (paraphrasing Gertrude Stein on Oakland).

Back then, I was reporting on the city’s new plans for Metro Pulse, and hopeful about the new ideas.

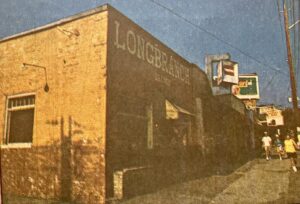

The city’s plan, which first emerged during the Haslam administration, was to dramatically redirect the lazy front-side parking lot habit by forcing new commercial construction up to the sidewalk, where all the stores and restaurants had been in previous generations. Thirty years ago, pedestrians strolled down the sidewalk from the Torch to the Roman Room to the Longbranch to Stefano’s, passing dozens of other front doors along the way, hardly encountering a single parking lot or chain eatery. Form-based zoning, respecting the capabilities of streetscape and architectural design over specific business restrictions, demanded that new construction connect to the sidewalk, as was the universal expectation in cities for centuries.

(Knoxville Journal Archives via KnoxTnToday.com)

A big part of the plan was to enliven the sidewalks by bringing back the residents. Cumberland had once been a mainly residential street, and residential density is a proven driver of urban life. Along with the form-based code was a related mandate that buildings serve multiple purposes, typically residential and retail. Altogether, the new plan seemed, literally, a prescription for the Cumberland Avenue we knew long ago.

When I was first familiar with Cumberland Avenue, as a footloose teenager, almost half a century ago, there were still a few houses and apartment buildings on the Strip. Most of the houses had turned into restaurants like the legendary Cat’s Meow, where you could eat or drink out on the front porch, and hail friends on the sidewalk—or retail, like Mary Gill’s import gift and fashion shop. But I remember the little cottage near 19th where an old lady lived, unbudgingly, in the middle of the nightclub district. She lived just as she would have in Sequoyah Hills, with a garden and big trees in the yard, and supported the Strip as she knew it in her own way.

There were other sorts of Strip residents, too. Back then, my favorite rockabilly band lived above the beer store where some of them worked. They weren’t trying to be an urban prototype for this new plan, but they were. With mixed-use construction, residents would come back, and the sidewalks would be lively with commerce again.

A redesign of the streets, with new medians landscaped with greenery, was meant to make it safer and more appealing to pedestrians. Some commuters complain that they’re so angry they’re not even going to drive that way anymore—perhaps unaware that discouraging drive-throughs was what the planners were promising us, 15 years ago. Avoiding Cumberland as a route from downtown to West Knoxville was exactly what they want you to do. And that in itself probably makes West Cumberland much nicer and safer than it was a while back.

But something else is going askew.

***

Some of the reaction is to the new buildings themselves. West Cumberland’s several enormous new residential buildings designed more for maximizing population than for esthetic admiration. Architects say they look cheap, even “temporary.” But they’re making it possible for hundreds more students to live near campus.

As of this week, Copper Cellar is still there. At almost 50 years old, it’s arguably the oldest sit-down restaurant in central Knoxville. Nothing downtown is quite as old. To suggest some context to its story, one of its early patrons was Boston-bred poet Robert Lowell, author of “For the Union Dead,” which was in lit textbooks when I was in college. He had several drinks there in 1977 to fortify himself for what would turn out to be the final public reading of his entire career.

But word has gotten around in recent months that Copper Cellar is soon to close, for the construction of another luxury residential building for students: another giant upscale private dorm.

What’s being built has just enough color and variety of material to avoid looking utterly blank. But will they ever be admired? Historically, it’s difficult to predict what architecture will be seen as worthwhile. Maybe someday people yet unborn will look at this buildings and say, “That’s so Twenties,” and find them charming. But that’s assuming they’re being built to last long enough to go out of style.

***

The assumption has been that these giant building programs are what killed the Cumberland Avenue so many of us remember. Those between the ages of 40 and maybe 80 remember when the Strip was the most fun part of town.

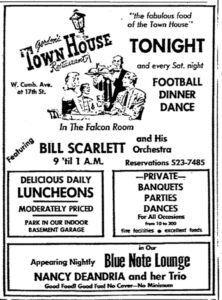

The list of bands who played live in bars on the Strip, many before they were famous, is liberal and long. That almost chaotically diverse array includes punk bands Black Flag, the Circle Jerks, and the Minutemen, but also Jimmy Buffett’s Coral Reefer Band, which was reportedly formed on the Strip in the early ‘70s; and Alabama—called “the Alabama Band” before their first hit, they were monthly regulars at one capacious bar; as well as the Stray Cats, the Romantics, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, there more than once—and REM, who played bars on Cumberland at least three times in their arena-bound career. Occasionally, a performer recognized on the street would surprise us with a visit, from Gregg Allman to Frankie Valli to Iggy Pop. That’s not even mentioning all the local bands that went places, like the Judybats, R.B. Morris, the V-Roys, Scott Miller, Superdrag, Immortal Chorus. Long before all that, mainly at Gordon’s Town House 60 or more years ago, were some of the country’s great jazz artists, including Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and Stan Kenton.

Gordon’s Townhouse, 1961. (Knoxville Journal.)

But for a few decades, young people would just wander down to Cumberland to have a beer and a pizza, play some pool or pinball, and see what friends and conversations they might find down there.

***

The Strip was the happening place. But as it was happening, something happened to it. Several things, actually, most of which seemed like good things at the time. Raising the drinking age from 18 to 21, accomplished by degrees between 1979 and 1984, was one of those. The drinking age both increased and, in years to come, got much more strictly enforced than it ever was when it was just 18. Those new laws and guidelines promised to save thousands of young lives from drunk-driving accidents, and maybe they did.

They also yanked the rug out from under the business plan for most of the Strip’s bars, restaurants, and nightclubs, especially those appealing mainly to college students. You could still have bars near campus, but you’d have to accept that your clientele would be limited to adults, which at UT is seniors and grad students, a minority of the whole student body.

Then, lest we forget, the late ‘80s was getting more and more competition from an unexpected quarter. When I was in college, over 40 years ago now, we just never went downtown, which was perceived vaguely, when perceived at all, as a place for old people, whether old bankers or old lawyers or old winos. A few years ago, a friend of mine, former editor of the Daily Beacon, was in town, and I suggested we meet on Market Square. “What’s that?” He said. He’d never heard of it. Of course he hadn’t. He’d left town in 1980. Back then, downtown wasn’t on our radar.

But beginning slowly in the 1980s, first with the Bistro and then bars and nightclubs of the Old City, then in the ’90s with Tomato Head and Market Square and the city’s first big brewpub. By the turn of the century, downtown had more good bars than the Strip ever did.

What people remember as the Strip’s golden age, the 1960s to 1980s, was the period when downtown was severely dysfunctional. Could the two both thrive as nightclub districts at the same time? Maybe so, now—but it’s never happened before.

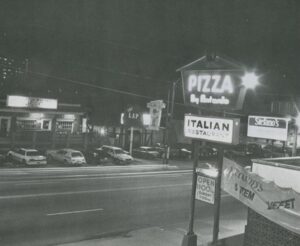

The Strip, 1986. (University of Tennessee Libraries.)

Another issue is that thanks to the expansion of Fort Sanders and the northern fringe of UT’s campus as well as the Mountcastle Park area—in some cases the expansion is just for parking garages—collectively resulting in a loss of hundreds of residences between 1990 and 2015, there were fewer people living within a five-minute walk of Cumberland than at any time since the 19th century. If that wasn’t the major factor, it didn’t help.

***

When I cheered on the new plan, somehow I assumed they would leave the functional landmarks, the places that might remind us it was still old Cumberland Avenue. It never occurred to me that the new developers, enabled and encouraged by smart city planning, would be removing buildings and thriving businesses that were already compliant to the carefully expressed ideals intended to revive the Strip.

In that big city initiative, was there ever any plan to save the functional parts of the stretch? I should have asked. At the time, the prospect of major developers playing within the city’s new guidelines seemed mainly theoretical.

The city plan seemed to be a good idea to me at the time. Maybe because they were worried about attracting developers who wanted to play by the new rules, the plan didn’t include a rigorous architectural standard. And it offered little or no incentive to preserve the Strip’s urban landscape, or the stable businesses that were already adding something positive to the mix, including durable history and character.

These western blocks of Cumberland weren’t necessarily notable for their architecture. Some were distinctive, lovable jumbles of buildings, like the block that included Stefano’s on the ground and the original Ruby Tuesday, entered from the side street behind and above. From that humble origin it was the very first of what would be, at one time, more than 650 Ruby Tuesdays across the United States and in a dozen foreign countries, reaching around the world from India to Hong Kong. Some things have shifted, but there are still more than 200 Ruby Tuesdays beyond East Tennessee. You’d think the very first location, in 1972, when it was an eccentric, lightly countercultural option on the Strip would be considered historic in business circles, and maybe worth teaching in UT’s school of business. Before any of us had heard the term “fern bar,” or experienced the concept, it seemed almost revolutionary.

But that old space was torn down a few weeks ago, along with Stefano’s and an old fancier restaurant space I remember as Antonio’s; I’m sure other generations older and younger remember these things by other names.

Stripped of the buildings that people remember, is it still the Strip?

The Strip, 1990. The Last Lap and Stefano’s are across the street from Antonio’s. (University of Tennessee Libraries.)

We’re not only losing actual businesses of long standing, like Copper Cellar and Stefano’s, but we’re also losing buildings of unremembered purposes, and the half-forgotten locations of Bundulee’s/Discount Records/Gabby’s, Old College Inn/the Pub, the Library/U-Club/Brewery—and the Last Lap. A few years ago, long after the seemingly immortal Last Lap closed, I was surprised to notice that the building was still there, just obscure in a way it had never been when it was Knoxville’s most popular bar. But then, not long afterward, when I looked again, it was gone without a trace.

Well—is it still the Strip?

There’s hardly anything for fathers to remember to their freshman sons and daughters. You can still point to where something was, but without much certainty. One of the most storied streets in Knoxville is becoming a place without memories.

Sam & Andy’s, the Last Lap, Ruby Tuesday, the original Longbranch, Hobo’s, Bundulee’s, Vic & Bill’s, the Vol Market, the Townhouse, Schoolkids’ Records, the Trestle Beer Store—they’re all gone, not only as businesses but as physical structures. Unless they’re artfully disguised, none of their walls are still standing. The Old College Inn’s prewar brick building, once frequented by Peyton Manning and Johnny Knoxville, and known in the ‘60s and ‘70s as Brownie’s, is still intact, now home to Sunspot’s second and current location.

Perspective on the Strip changes with the observer. What Baby Boomers remember isn’t what older people remember.

Those who remember West Cumberland in the 1940s and ‘50s remember it differently than people my age. To them, it was a sort of downtown Mayberry, a family commercial center mainly aimed at the people who lived in houses in Fort Sanders, with hardware stores, furniture stores, drugstores, the Studebaker dealership, and the mute man who sold shoes. The Booth was a cozy movie theater where kids felt comfortable, and a couple of family restaurants, some of them run by Greeks, like Sam & Andy’s, who introduced pizza to town in the late ‘40s, became legends. Dugout Doug’s record store was where two high-school kids named Everly discovered a new thing called rock ‘n’ roll by way of a new record by an offbeat character named Bo Diddley. UT students sometimes ventured this way, but didn’t dominate. I’ve been told Cumberland Avenue got more traffic from the thousands who worked at the Fulton/Robertshaw factory; they’d amble up the sidewalk at lunchtime to get a bowl of chili or a plate of Metts and beans at Brownie’s. In those days, Cumberland’s nightlife was mainly at Ballis’s poolhall, the longtime institution run by a Greek former prizefighter.

The Booth Theatre, Cumberland Avenue, 1928. (McClung Historical Collection.)

There were several automotive shops, tire stores, etc., which may seem surprising until we remember that it was once part of the junction of two national routes, the Dixie and Lee Highways; a lot of people who spent money on West Cumberland weren’t planning to spend the night in Knoxville.

Before that, in the ‘30s, it was home to WROL studios, when the Tennessee Chocolate Drops performed on the air even before Cas Walker was broadcasting, and Yon’s Spaghetti Shop, Knoxville’s first Italian restaurant, run by an immigrant marblecutter’s family.

Before that, a century ago, say—it was mainly a residential street of houses and a few mansions, mostly for the affluent, the O’Conners, the Cowans, the Kellers, the Woodruffs.

Before that, it was a dusty country road downhill from the occasionally visited ruins of a big Civil War fort that sustained a bloody siege.

It has changed with every generation or two. Each generation reinvents the Strip in its own image, and has found reason to be skeptical of what came after.

It’s not clear whether the Strip is ever as famous as it was, briefly, in May, 1970, when it was central to massive student demonstrations associated with the antiwar Strike, and early 1974, when there were spells when many of the people on the Cumberland sidewalk were stark naked. Or whether it will ever be a late-night crucible of musical creativity, hosting groundbreaking musicians on their way to national or global fame, as it was for a relatively short period of its history.

The slick new buildings that line West Cumberland now, with more to come, will never be striking or beautiful works of architecture. Nor do they suggest the endearing qualities of cobbled-together clusters of brick, wood, clay, stucco, and tin structures that characterized the Strip for decades. These big new buildings seem designed to shed any taint of the legendary.

But maybe that’s just this aging observer’s opinion. The Strip may have more incarnations in decades to come, with identities difficult to imagine today. Humans are nostalgic by nature, and each generation tends to create its own golden age.

Jack Neely, March 27, 2023