The Old Red Schoolhouse

Peabody School, Knoxville’s first public school, later known as our Labor Temple, is in peril

On a broken segment of half-forgotten Morgan Street is a building not like any other downtown. It’s getting a lot more attention lately, partly just because its once-obscure neighborhood is now adjacent to a popular new baseball stadium, and people walk by it on their way to and from games.

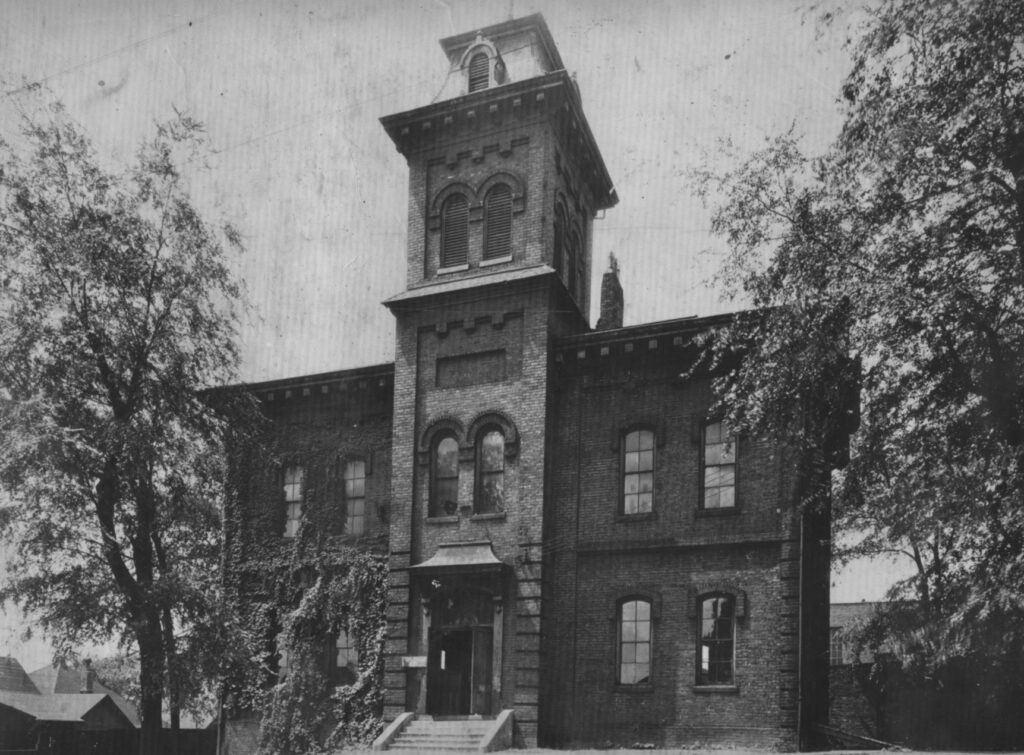

It’s a stout red-brick building, its style offering a strong hint of the French Second Empire, with a vertical towerlike projection in the center of its façade, and a roof sloping on all four sides. It was once taller, because it featured a belfry at the top. It’s hard to know what that looked like, since that uppermost feature of the tower was removed over 70 years ago, and photographs of the building before then seem to be elusive. (Since we posted this story, KHP friend Perry Childress sent us a photograph, from a file at the East Tennessee Community Design Center) of the old school building with its original tower. See the end of the story.)

The tower that remains features a plain sign that identified is with the AFL-CIO, the once-formidable national union that coalesced in 1955. It was about the same time that the belfry was removed, and those two large, blocky ground-floor extensions appeared in front, practical modernish expansions of the building’s square footage, including an additional auditorium. A former generation knew the building as the Labor Temple, a term unfamiliar if not alarming to those unaccustomed to thinking of labor unions in religious terms.

The local AFL-CIO and several other labor unions that once used this building have moved to other places, mostly far outside of downtown. In recent years, the politically active have known this old building as the Democratic Party’s local headquarters.

Knoxville is just rediscovering it. Several people, seeing it for the first time on the way to a ball game, have asked me about it. But a massive development scheme proposes to make it vanish.

***

Despite the additions and changes of identity, it doesn’t take much imagination to picture the building as it was.

The old Labor Temple was originally a schoolhouse. In fact, the first schoolhouse ever built for that purpose in Knoxville history.

It was known for half a century as the Peabody School.

***

It was, 150 years ago, the subject of some controversy. In the 1870s, there were still people in Tennessee who opposed the very idea of public education. Although by then the image of the little country schoolhouse was already a sentimental American ideal, with the schoolmarm with her handbell—she was a reality in some parts of the nation—in much of the recently Confederate South, she didn’t exist, and the very idea of public school was considered dangerous. You want to educate your kids, the thinking went, pay for it yourself. Nobody’s stopping you. Public schools bound to expand government’s franchise of government beyond its boundaries, which before then were basically running the courts and the jails and occasionally building or fixing a road, although private enterprise was often involved with that.

Working people were working people, they said, and it just didn’t do anybody any good to teach some of them to read.

Some of that thinking changed after the war, even among conservatives, for an ironic reason. Various philanthropies, religious and not, were funding new schools for Black people, the recently emancipated who had known few or no opportunities to learn. Now on their own, Black people would need to learn to read and do basic math just to find jobs and run businesses. So by 1868 or so, there were free schools for Black children. White families of the same era paid tuition to send their kids to private schools—when they attended school at all, and many didn’t.

Knoxvillians began looking around, and saying, shouldn’t there be free schools for white children, too?

The problem, as is often the case, is that nobody wanted to pay for it. An answer came from a surprising source. Born in poverty in Massachusetts back in 1795, George Peabody developed a genius for banking, and in 1837 moved to London, the global financial center, where he spent most of his adult life. In partnership with an American financier named J.S. Morgan, he developed an international superbank. J.S. Morgan was the father of the heir later famous as J.P. Morgan. Thus Peabody became the godfather of what later became known as JPMorgan Chase.

It’s hard to ignore the fact that, J.P. Morgan himself had a major impact on the destiny of this neighborhood. In 1894, the New York financier created the Southern Railway, buying out Knoxville’s impressive East Tennessee, Virginia, and Georgia line, but magnifying options for Knoxville rail customers, many of them clustered along the Jackson Avenue corridor.

So Peabody School on Morgan Street is named for the partner of J.P. Morgan’s father. (Lest we jump to conclusions, though, it appears that Morgan Street had that name before any major financiers had an interest in this neighborhood. Author Allen Coggins cites research suggesting it’s named for Rufus Morgan, an early developer who sat on Knoxville’s first Board of Aldermen in 1815, or his descendants who remained interested in that neighborhood.)

Peabody never married, but even in England, remained concerned about the fate of his fellow Americans, and by the 1850s, was beginning to share his wealth, especially for the cause of public education. His largesse was becoming well known before his death in 1869, but he became if anything better known after his death for his bequests of many millions of dollars for educational projects in America.

***

Taking a strong hand in this school-construction project was another surprising bi-national figure.

Mayor Peter Staub, a Swiss immigrant who traveled back and forth across the Atlantic several times in his career, working as a Swiss consul in America, as a U.S. consul in Switzerland, or sometimes as a World’s Fair commissioner in Paris, took the reins and pushed through the construction of Knoxville’s first substantial public-school building.

Staub, who crossed the ocean many times in his life, had gotten to know Napoleon III’s reconstructed Paris. It may not be a coincidence that the style of the city’s first schoolhouse is not just another Victorian building, but akin to Staub’s most ambitious project. Staub’s Opera House, East Tennessee’s grandest auditorium, was a Gay Street palace in the grand Second Empire style. Built in 1872, shortly before the school-construction project, Staub’s was the first impressively large and moreover stylish building ever built in Knoxville.

As mayor contemplating a school, Staub perhaps didn’t have quite as much money to work with as he did when proposing a grand opera house with multiple balconies and seating for more than 1,100, and likely to be profitable. But his fingerprints may be evident on the Peabody School.

To design it, he recruited the same young architect who designed the opera house. Newspapers rarely credited architects for their designs in those days, but in this case, J.F. Baumann, the first Knoxvillian to bill himself as an architect, got a nod in print, even if his name was misspelled in the story. Son of German immigrants, he was 28 when he transitioned from a profession as builder to building designer. Baumann was the founder of an 80-year dynasty of architecture firms that include Baumann Brothers and Baumann & Baumann.

About 30 when he designed this school, he had become notable for Staub’s Opera House, and for the extravagantly Victorian Locust Street home of financier-industrialist C.M. McGhee. The opera house was torn down 70 years ago. The McGhee house survives, but with its exterior altered almost beyond recognition, with all of its 1870s Victorian flourishes removed, and reframed soon after McGhee’s death as a sort of neoclassical building, for use at the 20th-century Masonic Temple.

Although considerably altered, too, the Peabody school may be Baumann’s oldest mostly intact work.

“Built upon an eminence, with its tall tower, it is conspicuous from all directions,” reported the Daily Press & Messenger of the new building Staub and Baumann created. “The rooms are all large, light, and well-ventilated, being each 14 feet high.” Much of that was apparently in sharp contrast to the cramped hotel rooms of the Bell House, which has housed a de-facto school for a couple of years before.

The opening of Knoxville’s first new school building, on April 20, 1875, was cause of much celebration.

An unsigned editorial in the Daily Press and Herald hailed it. “As this school is an institution to stand perhaps for centuries, while yet in its infancy, before its swaddling clothes are removed, before it grows to be a mighty giant of good, its christening is a matter of importance.”

And that christening was something to behold. At 9 a.m., Mayor Staub and his Board of Aldermen—which included several who had been born in Europe and several who would be major figures in Knoxville history, among them Peter Kern, George Albers, Samuel T. Atkin, and Patrick Sullivan—led a walking procession from the Bell House School to the exciting new Peabody School. Among them was alderman Daniel C. Hommel, a much respected teacher at Tennessee’s famous School for the Deaf, who led the building committee.

“As the procession moved along our principal avenues, it attracted great attention, and the corps of teachers with the hundreds of neatly dressed and bright-eyed pupils of both sexes, commanded the notice and favorable comment of our citizens,” reported the Press & Herald. The paraders congregated on the front lawn before the school, whose “gateways were festooned with evergreens.” The students sang songs, “Music in the Air,” and “Hark Away.”

Lawyer-publisher John Fleming, a Unionist during the war but a conservative one who split with the radicals of the Republican Party, was there because he was one of Knoxville’s most eloquent speakers and represented the fact that the conservatives were finally accepting the necessity of public schools. He made the point that Knoxville had emerged from its regional bias against public education to become a leader in schooling.

“In former times we regarded free education as the peculiar property of a people antagonistic to ourselves,” said Fleming, specifically referring to New Englanders.

“The educational facilities of the town were left to private enterprise alone.”

However, Fleming observed that lots of things had changed for the better in East Tennessee, crediting the trauma of war. “The children who grow up within sight of this building will feel they have a blessed heritage,” he declared, just as everyone was still waiting to have a look at the interior. “Here they have a fountain to which they in common with all the children in the city may come and drink of the waters of knowledge.”

And that they did for the next 50 years.

Almost instantly it was overcrowded, with 251 students by the end of 1875, some 60 more than anticipated. Over the years, if we can trust some spot-checking, it appears that its students were more than half female. Some boys presumably either worked or went to private schools.

All those girls and boys were attending school here even before J. Allen Smith built his flour mill a few blocks to the west, before Patrick Sullivan built his landmark saloon. Before, in fact, any of the buildings we know as the Old City. The Peabody School is the oldest.

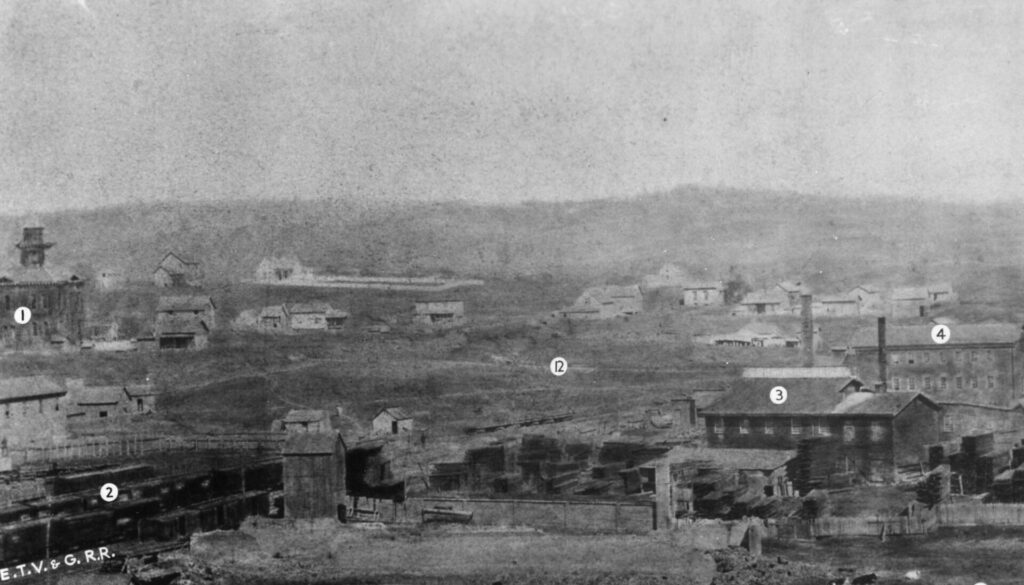

Looking east from Gay Street, circa 1877, with the Peabody School identified by #1 on the far left of the image. A very rare image of the building when it was operating as a schoolhouse. The oldest structure in the Old City area, Peabody School is the only building in this photograph that still exists. (McClung Historical Collection.)

For the next 50 years, Peabody School was Knoxville’s north-side school. References to it in “North Knoxville” might be surprising today, until we realize that when it was built, the city’s northern limits were just a couple of blocks north of Peabody School.

A list of students who attended Peabody School would number in the thousands, and would surely include people we’ve heard of. That may be a research project for another day.

At least partly green fields in 1875, with immigrant Irish Town crowding around the fringes, the school’s neighborhood in the early 20th century slowly became a place of slaughterhouses and packing companies and, at night, of vice and violent crime. In 1900, the city’s first legal red-light district emerged just three blocks away. As time went on, a women’s shelter nearer the school was evolving into a de-facto women’s prison.

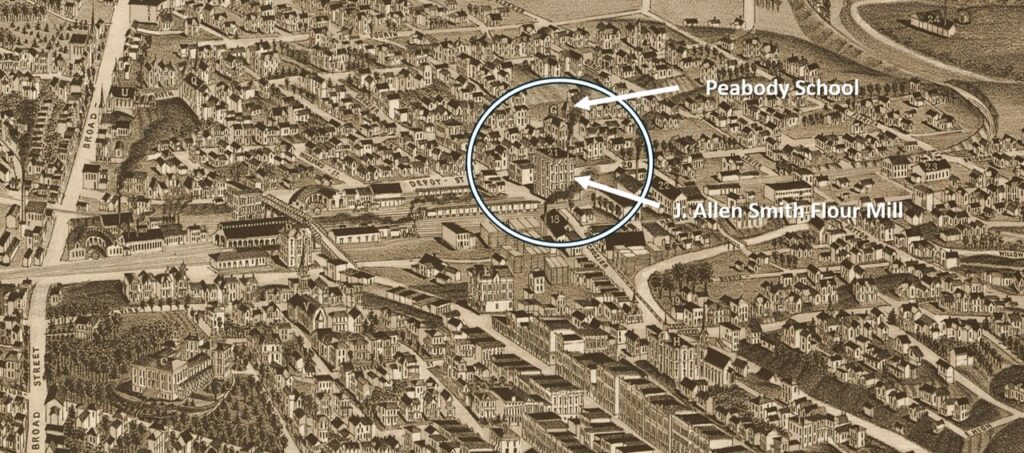

A detailed view of Knoxville map of 1886 showing the Peabody School (G) just north of the J. Allen Smith flour mill (21). (Library of Congress.)

And by 1925, Knoxville was suburbanizing, and schools were modernizing in design.

Not long after the school closed, in the early days of the Great Depression, when thousands of East Tennesseans were looking for work, the Central Labor Union purchased the old school and rechristened it into as the Labor Temple.

To anyone under 70, the term may sound crypto-religious. It’s not used much anymore. Google sources suggest the phrase “Labor Temple” peaked in usage nationally between 1910 and 1950. Today, you rarely hear it. But in the ideal, a Labor Temple was a specialized community center, owned by the unions but open to the public and to political gatherings.

At its dedication was a different selection of Knoxville big shots than had been there 55 years earlier for the school opening. One of the best known was John T. O’Connor, the former boxer, machinist, and labor leader, who had grown up just around the corner in Irish Town. He would soon be elected mayor of Knoxville, and was a popular one, whose ideology folded in well with the New Deal. In his long life, he would live to see the city’s new senior center open in his honor.

In its heyday, published claims cited as many as 100 trade unions sharing this one building, to different degrees. They called strikes here, sure, but they also offered job training and placement. They planned Labor Day events here, back when Labor Day was about labor, about being proud of what you do for a living. The Central Labor Union planned big parades of as many a 4,000 union members on Gay Street, marching alongside their colleagues by trade.

Although built to be capacious for hundreds of children in knickers and ruffles, the building proved less than ideal for some modern labor events. They needed more space than the now long-deceased Baumann had planned, and in 1954—just before the formation of the AFL-CIO, the largest of the unions that met here—the unions added the practical if ungainly extensions to the entrance—and also removed the old 1875 belfry.

Meanwhile, in the 1980s, as unlikely as it might once have seemed, the Old City, the old saloon and warehouse district only recently known by that name, began to revive as a restaurant and entertainment district. In 1983, the same year Annie’s opened on Central, the union who owned the building announced an attempt to get it on the National Register of Historic Places. I’m not sure what became of it—was it doomed by its big blocky 1954 extensions?—but it’s not on that list today.

The new nightlife fun over on Central sometimes expanded to the east, but never quite reached Morgan Street to suggest any other fate for the old Peabody School. Most of the union activity dissipated or moved to suburban locations, and the odd old building, by whatever name, got quieter.

The old Peabody School / Labor Temple eventually fell in the hands of Knox Rail Salvage, which, to be kind, is not known for fixing up old buildings.

I’ve often taken the unsuspecting on walking tours over there. People were surprised to see the big building suddenly appear on its “eminence… conspicuous from all directions.” Most folks say they’d never seen it. It has become inconspicuous, hard to see from any distance—but as you approach it on foot, it still impresses, as it did during the Grant administration.

Things are different now, thanks to the new ball park. Several evenings in the summer, hundreds of people walk by it, to and from the stadium from their parking places, and wonder what it is, and what will become of it.

I’ve been expecting something interesting or even fun to happen to the old building. Here in town, several of our old, once-abandoned schools, from Eastport to Oakwood to South High to Knoxville High, have been successfully reborn as residential buildings. Meanwhile, historic Labor Temples from Philadelphia to Peoria to San Diego to Seattle have become trendy and attractive and in some cases famous nightspots, some of them with interpretation honoring the history of the building.

Maybe I’m naïve. I was expecting something inspired to happen to this historic landmark when people learned it was there. I’ve gotten spoiled by local architects surprising me with something better than I expected. But I’m starting to think the era when everything new that happened in downtown Knoxville was mostly good, and a credit to the city’s history, is coming to a close. People who don’t understand the old stuff are swooping in to do something like they saw in Atlanta 20 years ago, and make a quick buck. Or a few million of them.

The old Peabody School, Knoxville’s first-ever public school, and one of Joseph Baumann’s first known works, is part of a five-acre parcel that’s for sale for many millions of dollars. Described as “one of the last large-scale development sites in the heart of downtown Knoxville … ideally positioned for a transformative urban project.” Mentioning “unlimited height and density,” the suggested use is high-rise housing or hotels.

In an image intended to attract investors, there’s no old school at all. Other buildings, like a handsome early 20th-century warehouse building, are gone, too. There’s a century and a half of the history of an especially interesting corner of town we’ve neglected and forgotten for years, just erased, without stories to tell.

By Jack Neely

A photograph of the Peabody School with its original tower. Special thanks to Perry Childress and East Tennessee Community Design Center.)