1982 Worlds Fair in Hindsight

Was history made in Tennessee?

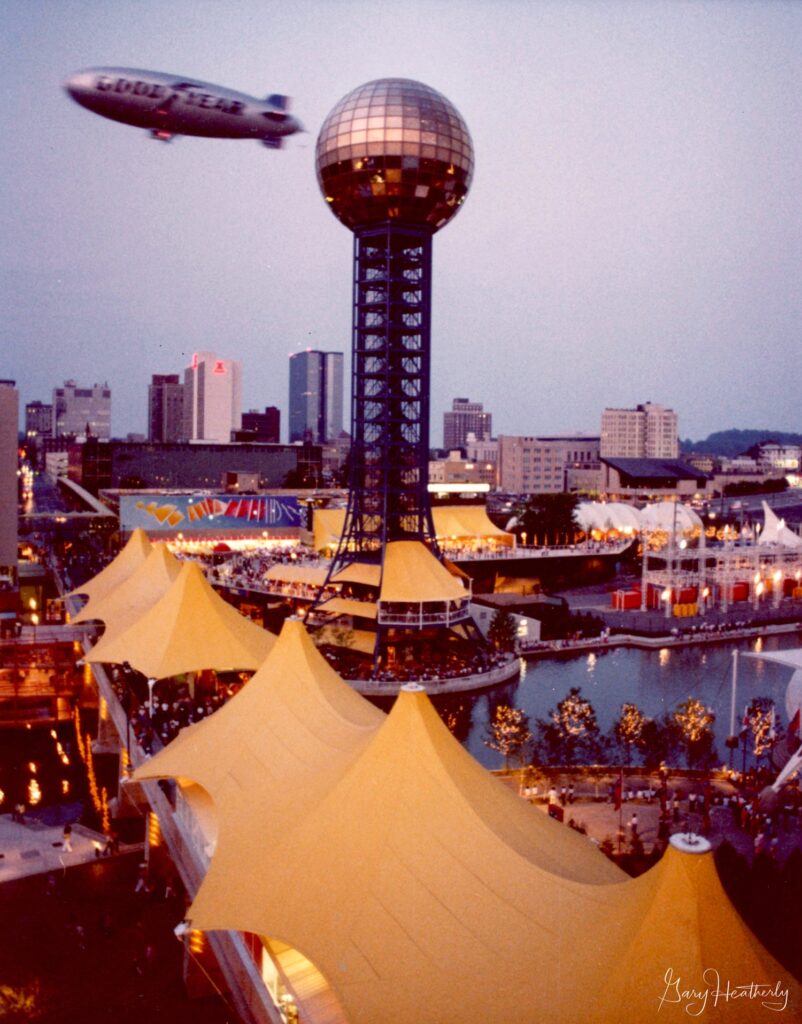

Even today, you can’t miss the 1982 World’s Fair. Driving through town on I-40, without even slowing down, you see that big gold ball and have to wonder what that’s all about. Most Americans aren’t old enough to remember those surreal six months of 1982 when Knoxville had the temerity to host a real World’s Fair. And those who do tend to remember personal things, moments of fun with family members, deely bobbers, World’s Fair Beer, and the “chicken dance.”

But back in 1982, a television ad shown across the country, promised, “If you want to see how history / Is being made in Tennessee / You’ve got to be there!”

Was history made at that memorable party? The answer doesn’t come quickly. The event is mentioned in very few histories or biographies. It’s absent even from some book-length histories of world’s fairs, which tend to focus on the grander and more ambitious big-city expositions. But the world’s fair was more than 1,000 different things, some of them silly, perhaps some of them more relevant. Maybe it has just taken time to digest what did happen there.

America saw several innovations for the first time that year, some that never amounted to much, but a few that did. In fact the 1982 World’s Fair had a serious, in fact, urgent purpose—and how it unfolded reflected the global anxieties and ever-shifting alliances of the Cold War. The 1982 World’s Fair presents a picture of several major nations at turning points in their histories.

It began as a thoughtful response to the 1973-74 Energy Crisis, which itself was a result of the Yom Kippur War in the Middle East, and the consequent Arab oil embargo of Israel’s allies. Gasoline prices tripled in the United States and presented a major problem to solve.

The Energy Crisis happened to coincide with the 1974 Spokane World’s Fair, which had an environmental theme. At the time, that city in Washington state was the smallest American city ever to host an international exposition. Although few Knoxvillians made the 2,300-mile trip to see it, some influential ones did. W. Stewart Evans was the director of the beleaguered Downtown Knoxville Association at a time when downtown seemed to be disintegrating. In the mid-‘70s, anchor retailers were abandoning downtown for suburban mall and strip-center locations. Downtown’s two surviving movie theaters were struggling, both soon to close. Evans, an Illinois native, was a retired Air Force colonel in his 60s, who had recently worked as a university events administrator. He regarded the Spokane fair, put on by a city about Knoxville’s size, as a challenge.

It was just as that fair closed, in November, 1974, that Evans gave a seemingly modest talk to his downtown group, suggesting that Knoxville had so many associations with energy research, through the University of Tennessee, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, and the Tennessee Valley Authority, that the city could credibly be posited as a national energy center—and, with that identity, host a credible energy-themed World’s Fair, as early as 1980. Knoxville’s second advantage was that, unlike some postwar fairs with disappointing attendance, its location, at a major national interstate intersection and central to the most populous third of the United States, would guarantee attendance in the eight digits. And the best place for it was the semi-abandoned industrial corridor and freight yards on the western side of downtown, along Second Creek.

It was just a “blue sky” idea, he said, but it leaked out pretty quickly and became something more.

His proposal was perhaps not as outlandish as it seemed. Knoxville products, especially marble, were heralded at America’s first world’s fair, in Philadelphia in 1876. Prominent Knoxvillians had served as commissioners or jurors in major expositions in Paris from 1878 to 1900—and at the extremely influential Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. The 1900 Paris exposition, in particular, featured a gallery of photographs of prosperous African Americans in Knoxville. Many Knoxvillians attended the famous St. Louis fair, a daily topic of conversation on Gay Street in 1904. By 1910, Knoxville was inspired to mount large regional and national expositions of its own, at Chilhowee Park. The largest of them, the National Conservation Exposition of 1913—to which the subject of energy was certainly germane—drew more than one million visitors in its two-month run, including multiple leading reformers of the era. It was such a sensation that in retrospect the NCE has made some speculative lists of expositions that approached world’s fair status. However, the legacy of the NCE was hardly mentioned in the planning of the Energy Exposition to be held 69 years later.

In 1975, Evans’ logic about Knoxville as an ideal city for an energy-driven exposition was persuasive. Within months, Mayor Kyle Testerman, Gov. Ray Blanton, Congressman John Duncan, Sen. Howard Baker, and Democratic gubernatorial candidate Jake Butcher were supporting the idea. A political leader but as a bank owner also a financial one, Butcher (1936-2017) quickly took a leadership role in the project. Enthusiasm was bipartisan. Joining these politicians and boosters early on was S.H. “Bo” Roberts, a developer, former UT administrator, and member of the Metropolitan Planning Commission. Formally it would be known as the Knoxville International Energy Exposition (KIEE).

President Gerald Ford’s secretary of commerce, Elliot Richardson, was interested, but discouraged Knoxville from holding a fair in 1980, as originally suggested, because it would conflict with another, much-larger World’s Fair planned for Los Angeles. After a meeting with Richardson, Sen. Baker, Evans, and Butcher got the go-ahead to plan a fair instead for 1982. Of course, the Los Angeles fair never happened.

By early 1977, their momentum convinced the Bureau International des Expositions in Paris that Knoxville had the wherewithal to host an energy-themed world’s fair.

International news reiterated the urgency of the energy theme in 1979, when the Iranian Revolution deposed the U.S.-backed shah, and suddenly America no longer had access to one of the world’s largest oil reserves. Gas prices rose again. The nuclear-reactor accident at Three Mile Island the same year underscored America’s energy dilemmas.

Aiming at 1982, organizers set about to gain commitments from corporations, entertainers, and especially international participants. Several western European nations, France, the United Kingdom, West Germany, Italy, Hungary, most of them accustomed to big expositions in their own nations, signed up quickly. Of course, West Germany, led by Chancellor Helmut Schmidt, was then still a very different place from Soviet-dominated East Germany.

Another early joiner was the young and little-understood European Economic Community, an unusual project to create a permanent cooperative economic bloc. It represented ten nations, including Belgium, Denmark, Greece, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands—as well as France, Italy, West Germany, and the United Kingdom, who were planning their own individual pavilions. At the fair, all 10 nations were considered full international participants in the fair, whether they also hosted an individual pavilion or not.

Greece had joined that alliance only the year before, and was represented at the fair. But 1982 had been a disappointing year for the EEC, which witnessed its first defection that year. Three months before the opening of the fair, Greenland split, proving its independence from parent country Denmark, and perhaps from Europe.

The EEC evolved into the European Union, formed 11 years later, soon to create its own currency, the Euro; Knoxville’s fair was the first world’s fair for which the EEC created a pavilion, suggesting one claim that the world’s fair may be historic.

***

The Soviet Union, led by Leonid Brezhnev, had participated in the Spokane fair and expressed interest in this one. For a time the USSR was expected to be the Knoxville fair’s primary anchor attraction. A 1979 Soviet sports exhibit downtown was seen as a good-will gesture in anticipation of something much bigger in ’82. But then the Soviets invaded Afghanistan, and in retaliation, President Carter withdrew U.S. participation in the 1980 Moscow Olympics. And the Soviets withdrew from discussions of the next American world’s fair, in Knoxville—as well as the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics.

China, little known and forbidden to westerners for most of the period since Mao’s takeover in the 1940s, had never participated in a western exposition during its Communist era. The world’s most populous nation was on nobody’s short list for the Knoxville fair. But in 1979, Deng Xiaoping, seeking better relations with the West and new economic opportunities, became the first-ever Chinese head of state to visit Washington. Soon after that came word that China might come to the party with a big pavilion. China signed an official letter of intent in October, 1980.

After the European early entrants, a grab bag of other nations agreed to mount exhibits: Japan, Australia, Mexico, the Philippines, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Canada, Egypt, Peru. Most of those later entrants, perhaps after some cajoling to get around the mandatory energy theme, presented exhibits that were mostly cultural, with only token nods to energy innovation.

There were last-minute worries about whether all would be ready, and some things weren’t. Panama had agreed to participate, interested in confirming its association with the United States after the controversial 1977 canal treaty, and announced elaborate plans for a working model of the canal to be part of the exhibit. But during the political chaos after Gen. Omar Torrijos’ death in a plane crash the previous summer, Panama never completed its Knoxville pavilion. Its 6,000 square-foot building, adjacent to Hungary’s, sat empty for the first half of the fair, but by August, it was home to a makeshift Eastern Caribbean exhibit, with a Green Parrot restaurant, steel drum performances, and a purely tourism-based theme. It represented five tiny island countries of the British West Indies, including Montserrat and Barbuda, each of them with small, enticing exhibits in the pavilion. But they offered no nod to the Energy theme, and after objections from other international participants who’d been there from the beginning, were not counted among the fair’s official international participants.

At least 10 sub-Saharan African nations were invited to host a pavilion or at least an exhibit, but University of Tennessee executive Theotis Robinson’s ideal of a pan-African pavilion was not as appealing to the nationalist governments he approached. The building reserved for them was turned over to late-entrant Australia. The African nations of Gabon and Nigeria had been interested in the fair, but never committed. Several dancing and musical groups from African nations, including Ghana, performed at the Tennessee Amphitheatre.

An African American pavilion, which was to feature a museum of achievement including Frederick Douglass’s desk, Harriet Tubman’s rifle, and Jesse Owens’ medals, was scotched for lack of a corporate sponsor. The efforts resulted in a much-smaller exhibit at the main exhibit hall, which included a Great Kings of Africa exhibit, a gallery of Black American leaders, and a film narrated by James Earl Jones. Disappointing as it was to those who hoped for a full pavilion, according to Black Enterprise magazine, it was the first extensive African American exhibit in the history of American world’s fairs. (That may be less surprising considering that it was only the second world’s fair in the era of affirmative action—and that its only predecessor, Spokane, had a tiny minority population.)

Civil rights activist Avon Rollins, a TVA executive who sat on the KIEE board, claimed that a large portion of the fair’s proceeds went to the African American community. The contract for the flame-logo World’s Fair T-shirts went to Upfront America, a Black-owned business, which produced and sold almost half a million of them that year.

***

Most world’s fairs are notable for architecture, whether permanent or temporary, from Paris’s Eiffel Tower to New York’s Trilon and Perisphere to Seattle’s Space Needle. For Knoxville, the theme structure was to be the Sunsphere, proposed in early 1980 by William Denton and Hubert Bebb of the firm Community Tectonics. Illinois-born Bebb (1903-1984) already had some World’s Fair credentials—he had been a young designer at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1933. After moving to Gatlinburg, where he designed the rustic Buckhorn Inn and worked on buildings at Arrowmont School—and, in 1955 the strikingly modernist viewing tower at the Smokies’ Clingman’s Dome, which remains both popular and controversial almost 70 years later. In 1980, Bebb’s conception of a tribute to the sun, the original source of all energy on Earth, earned the approval of the fair’s planners. Denton balanced realities of budget, site challenges, and an inflexible deadline, and still found a way to put the globe securely up in the air. Because it bore some resemblance to a geodesic dome, legendary architect Buckminster Fuller, then in his 80s, took an interest in it, and came to Knoxville to consult. Standing at 266 feet, the round part, then described as the world’s most perfectly spherical building, was faced with panes inlaid with gold dust, giving it a golden glow. Accessible by elevator, the five-story interior would include observation decks and a restaurant. It didn’t wow critics at the time. The New Yorker’s E.J. Kahn said it was “accurately likened by a number of critics to a giant golf ball on a tee.”

Knoxville’s venerable architect Bruce McCarty (1920-2013) had promoted modernism in Knoxville in the 1950s and ’60s, and oversaw the architectural look of the fair. For the state-funded pavilion, the Tennessee Amphitheatre, he enlisted the help of a German architectural engineer, Horst Berger (b. 1928), who had been experimenting with a new form of structure using tensile fabric, a rigid but adaptable covering. Not very well known at the time, Berger and his approach to design and construction have been used in several other works of architecture around the world since then, including the King Fahd International Stadium in Riyadh, Denver International Airport, California’s Sea World, and the Wimbledon Tennis Complex in England. The Tennessee Amphitheatre represents one of the earliest examples of his innovative structural approach. It received hardly any attention from national journalists.

Another new building was intended to be permanent, the U.S. Pavilion and its companion IMAX theater. Designed by the modernist Atlanta architectural firm of Finch, Alexander, Barnes, Rothschild and Paschal (FABRAP), who had also designed Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium and Coca-Cola’s Atlanta headquarters. The fair’s largest pavilion was intended to highlight American technological savvy. Ultramodern in design, the long, wedge-shaped six-story structure won an award from the Georgia chapter of the American Institute of Architects, but was less impressive to the New Yorker’s E.J. Kahn, the 65-year-old son of a prominent New York skyscraper architect, who wrote: “a slope-side six-story pile whose main distinction is that it is in part solar-heated and solar-cooled, looks like a factory that has been designed by the factory-owner’s son in law.” Celebrity critic Rex Reed, writing for GQ, called it a “six-level horror of glass and steel that looks like a giant gasworks gone berserk.”

Perhaps surprisingly, the 1982 World’s Fair became a showcase of historic preservation. Dramatically different from almost all previous expositions, it employed multiple renovated historic buildings. The 1905 L&N station, empty or underused since it served its last passenger train in 1968, was reborn as a restaurant and office complex. The associated freight depot housed a niche art museum. A foundry remaining from Knoxville Iron Company’s ca. 1870 plant became the Strohaus German-style beerhall. The old brick ca. 1915 Littlefield & Steere Candy Factory, used mainly as a warehouse since the Depression, saw new use as a mall of shops, with restaurants and bars—and, in honor of its heritage, the return of candy manufacturing during the fair. Seven modest 1890s Victorian houses along 11th Street were rehabbed for modest uses during the fair, including the Budweiser Beer Garden, a Victorian house with new outdoor porches stretching in the direction of the Clydesdale stables, just down the hill.

The World’s Fair’s preservationist ethic is remarkable, considering that historic preservation, as an ideal, was relatively new to Knoxville. Because many of the buildings were saved for permanent use after the fair, Knoxville’s fair site is perhaps more intact than most. Architect Charles Smith declared that preservation meant this would be the “most recyclable” world’s fair in history.

The New Yorker’s E.J. Kahn was also disdainful of all the fair’s new architecture, claiming “the imaginative architecture that one looks forward to at world’s fairs is sadly lacking,” but he added, “Two of the more beguiling structures are Victorian-style ones that were built in the lower Second Creek Valley around the turn of the century”—the L&N Station and the Candy Factory.

In a brief assessment of the fair’s structures, Architectural Record avoided specifics, mentioning “four new permanent structures of varying architectural distinction, a cluster of recycled buildings of varying degrees of period charm.”

***

The fair opened on May 1, and never got more attention than it did that day.

On hand was the cast of NBC’s “Today Show,” including Jane Pauley, Bryant Gumbel, and Willard Scott, who broadcast live from the fair for three days in a row, Scott giving the national weather from a lofty gondola. Joan Lunden of ABC’s “Good Morning America” was broadcasting there, too. Governor Lamar Alexander played a grand piano on national television, from Chopin to “Rocky Top.” Sen. Howard Baker, a UT alum who was then U.S. Senate majority leader, spoke. Singer Dinah Shore was there, and country star Porter Wagoner, and Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee.

President Ronald Reagan and singer Dinah Shore, along with several other dignitaries, were special guests at the opening of the 1982 World’s Fair on May 1, 1982. Courtesy of Visit Knoxville.

Also speaking that day was the president of the United States. Although cynics have raised the issue of whether Ronald Reagan would have supported federal funding for an energy-oriented world’s fair, he used the occasion enthusiastically, to urge Congress to pass his tax-cut initiatives, and to chide the USSR for not participating in the Knoxville fair. It was an example, he implied, of American openness with its knowledge and resources.

***

For many Americans, it was a first-ever visit to a world’s fair, and they came expecting something more astonishing than descriptions and demonstrations of energy conservation, efficient power plants, and alternative fuel sources—the diet of most of the international exhibits. The fair was hardly days old before the first public complaints that it was “boring.” That sentiment would be echoed by both regional and national journalists.

For those with the curiosity and patience to look for them, the 1982 World’s Fair included dozens of thrills, both physical and intellectual.

Those who made it to the south end of the fair site found the Great Wheel. Its claims to be the tallest “of its kind” in the world were perhaps a little misleading; the first famous Ferris Wheel, at Chicago in 1893, was much taller, as was an existing wheel in Vienna. But at 150 feet, it was a lot taller than the 40-foot Ferris wheels most people had seen at carnivals. Other rides, including gondola and chair-lift rides designed by European companies to take people across the almost linear north-south park, were less spectacular but just as popular.

The Tennessee Valley Authority, one of the major anchors of the idea that Knoxville could host a major energy exposition, built a unique and appropriately aquatic pavilion on a barge floating in the river near the mouth of Second Creek. It may have been the most child-friendly of the educational pavilions, as visitors who boarded the boat were invited to operate a toy-sized dam-and-lock system on a miniature waterway. The skipper of the vessel was the fictional “Captain Nat,” portrayed in person by Bill Landry, before his regional fame as host of WBIR’s long-running documentary “Heartland Series.”

Every single night of the fair witnessed both a fireworks display and a laser light show, a dumbfounding demonstration of colored beams piercing the skies and covering miles to the horizon; most humans had never witnessed such a phenomenon, but Knoxville got used to it.

There were fun little surprises here and there. The Petro, which was literally a split bag of Fritos with chili and other toppings on top, became a popular novelty.

One talked-about innovation available for sampling was a new kind of milk that did not require refrigeration. Those who tried it were unimpressed with the taste.

Kodak introduced its easy-to-use Kodak Disk camera at the World’s Fair. No computer disc, the term referred to a plastic wheel with tiny bits of film. Though nationally marketed for about three years after the fair, it did not catch on.

Without making any overt announcement, Coca-Cola used one refreshment stand installed at the China line that summer to test-market several different flavors of its classic beverage, including lemon, lime, chocolate, vanilla, and cherry. (Though unrelated to the “New Coke” debacle a few years later, the innovation may have had a similar origin; Coke’s once-dominant share of America’s soft-drink market was declining.) Long a fountain favorite, Cherry Coke was first bottled with the cherry flavor already in it about three years after the fair.

Several of the fair’s most substantive exhibits seem forgotten.

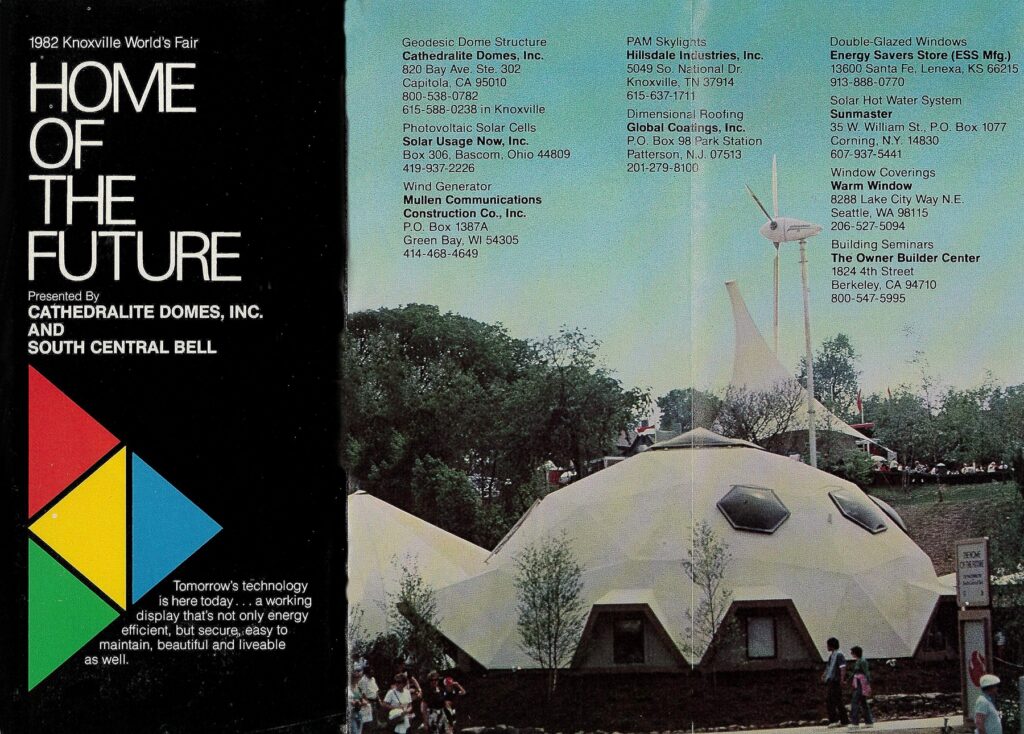

Corporate exhibits included Today’s Solar Home, exhibiting the latest in photovoltaics for practical use; elsewhere on site, there were “solar telephone booths,” with a solar panel on top, though in truth the sun powered only the light in the booth.

Cathedralite, a California-based company, hailed their example of a geodesic-dome home, the “Home of the Future,” advertised to reduce energy costs by one-third, mainly by its shape. A very different “Energy Saving Home,” retrofitted with improved insulation and other innovations, was demonstrated in one of the old Laurel Avenue Victorian houses on site. (One of the few journalists who described it apparently didn’t realize it was a genuinely old house, calling it “neo-Victorian” in style.)

South Central Bell’s exhibit, ignored by most visitors, offered a “teleterminal” which might one day allow consumers to do their banking and shopping from a computer at home. A COMSAT screen showed how in the future, video conferences might be conducted remotely—thereby saving transportation-energy costs.

A New York company called Cooper Associates showcased three electric cars. Press about the fair suggests that few noticed them.

The 1982 World’s Fair did include realistic displays of relevant new technology, innovations that did hint at electronic life in the 21st-century future. Whether poor placement or human nature is to blame, most people, including journalists, skipped them.

***

Live entertainment was a constant, all day, every day. Performers at the Tennessee Amphitheatre included soul/blues musician Richie Havens, who had opened Woodstock; surf rockers the Ventures; balladeer Dave Loggins; crypto-Western stalwart Slim Whitman; Met soprano Roberta Peters; guitar legend Chet Atkins; concert pianist Peter Nero; blues icon Koko Taylor; comedian-classicist Victor Borge; folk maverick John Hartford.

Ticketed shows at the Civic Auditorium featured Isaac Stern, Bob Hope, and the London Symphony Orchestra. Japan’s Kabuki Theatre, rarely seen in the United States, included Knoxville on its three-city tour that year.

A Broadway-aspiring show, The Conversion of Buster Drumwright, a musical version of a Jesse Hill Ford play starring Knoxville’s own Tony winning singer and actor John Cullum, saw 58 performances at the unrenovated Tennessee Theatre, rendering an attendance of about 25,000, probably still a record for a single dramatic production in Knoxville. Drumwright was later performed in Nashville, but never had the hoped-for afterlife on Broadway.

In this extravagant exposition ostensibly about the newest technology, the choice of musicians was impressive, especially in its diversity of international folk music, but couldn’t be considered cutting edge. The fair offered hardly a trace of rap, punk, New Wave, avant-garde jazz, or anything else that was considered new, or even recent, in 1982. Incidental music had a ’70s disco beat. Most of the fair’s mainstream American performers had peaked years or decades before; some were little more than nostalgia acts. One exception might have been when Jeff Lorber Fusion performed at the Amphitheatre in June; the 29-year-old jazz-pop keyboardist and composer would maintain a fan base for decades to come. (It’s likely that Lorber’s band included his longtime saxophonist, Kenneth Gorelick, who had just produced his first album, and would later be known as Kenny G.) Another outlier was the offbeat Australian rock band Men at Work, just then rising in popularity in America, who performed an unadvertised show at the Australian Pavilion.

However, the notoriety of the fair and the flood of young “carnies” into town likely played a bigger cultural role in an unprecedented musical surge outside the gates, as several clubs along Cumberland Avenue featured daring new national music acts. The Georgia quartet REM, which hadn’t yet released a full album, drew a crowd of about 200 for a show in a small bar called Hobo’s during the fair’s last month.

The Scottish National Orchestra performed at the Amphitheatre, as did the Prague Symphony, at a time when its host city, then the capital of Czechoslovakia, was occupied by Soviet troops; the Velvet Revolution was still seven years in the future.

Poland, led by pro-Soviet dictator Wojciech Jaruzelski, was suppressing dissent, symbolized by the two-year-old Solidarity movement, and was technically under martial law, and subject to sanctions by the West. Still, the Warsaw Philharmonic made its way to the world’s fair, and performed works of Rachmaninoff in the Tennessee Amphitheatre. When people in the audience raised a bold SOLIDARNOSC banner, the orchestra quietly communicated its assent by tapping bows on music stands.

The modest and often sparsely attended Folklife Festival, in a rustic venue on a quiet hill on the northern end of the fair site, welcomed country and blues figures of the past, as well as some of modern bluegrass’s up-and-comers, like Doyle Lawson. When he played at Folklife with his longtime bandmate Ted Bogan, former Knoxvillian Howard Armstrong was 73, but not yet the legend he became after Terry Zwigoff’s nationally broadcast 1985 documentary Louie Bluie. Another older performer there who became more legendary later was blues singer-songwriter R.L. Burnside, who was then 56, but still waiting for his peak in popularity in the 1990s, when he found a new audience of younger fans.

The number of acts, large and small, that performed at the fair is almost certainly in the thousands, if we include high-school and college marching bands who gave concerts at the Court of Flags, German-style polka bands performed at the Strohaus, as Australia’s Down Under Pub’s nightly bluegrass bands. Some nightclub-style performers appeared at the Flamingo Lounge, at the top of the Candy Factory.

The World’s Fair included token artistic gestures. The oils at the little-known fine-arts exhibit included a Murillo and an attributed Rembrandt. Near the Saudi Arabian pavilion was a mini sculpture garden, including Alexander Calder’s mobile “Red Dragon.” And the artist in residence was the psychedelic icon of the late ’60s, Peter Max. Although he inhabited his Henley Street studio for only a few days, from Knoxville he delivered a painting to the White House to celebrate the centennial of the Statue of Liberty. (He attended a reception or two with his singer-actress girlfriend Rosie Vela, but was later sued by the Pembroke for nonpayment of rent.)

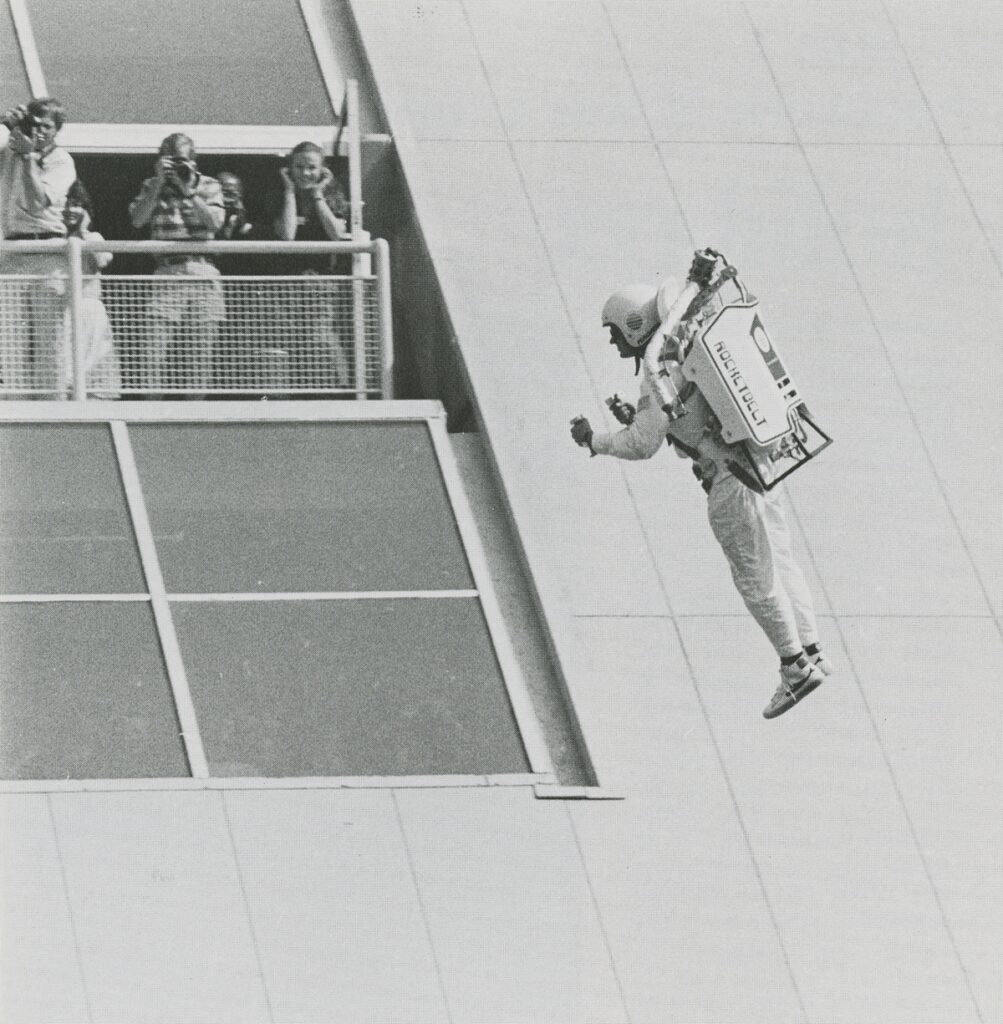

Some early visitors compared the fair unfavorably with New York’s rule-breaking, noncompliant World’s Fair of 18 years earlier, sometimes mentioning its most talked-about performance, the jet-pack demonstration. Aiming to please, fair officials enlisted one of America’s very few jet-pack pilots, Bill Suitor, to Knoxville, with what was claimed to be one of only two “rocket belts” in existence. Suitor made two 21-second flights each day over the water feature, Waters of the World, between the U.S. Pavilion and the Tennessee Amphitheatre during U.S. Week, in late June and early July. Rocket-belt technology had not improved since 1964, and could hardly be seen as an answer to any energy-efficiency dilemma, but it made a memorable spectacle. Perhaps, like many of the musical acts, it reminded crowds of a previous era, when it was featured on Thunderball, Lost in Space, and Gilligan’s Island.

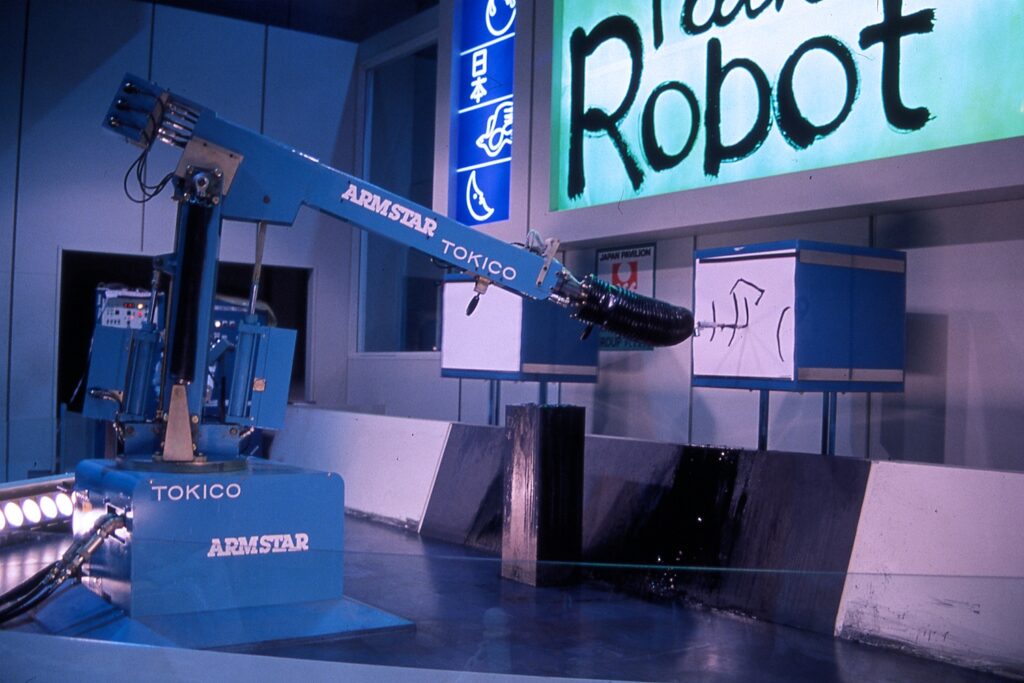

Japan, no longer a tiny nation struggling to recover from defeat, had created the world’s second-biggest economy, and had just surpassed the United States to become the world’s biggest automaker, becoming a serious rival on the global market for several U.S. products. Highlighting their technological wizardry, Japan created a pavilion offering both a virtual and heart-stoppingly realistic bullet-train ride and a painting robot with a flair for semi-abstract art. It was just a symbol of what Japan had learned to do with robots in factories.

South Korea’s pavilion included a performance space for its Korean folk dancers, rarely seen in America, whose daily performances were almost always sold out early; every morning, hundreds of visitors who’d heard about it swarmed the pavilion for tickets.

Australia built a set of aluminum windmills along Cumberland Avenue, and its pavilion included the Down Under Pub—located down under their building, of course—with real Australian blokes selling Vegemite sandwiches and big cans of Foster’s Lager. Mexico featured an earth-rumbling cinematic experience of a volcano’s eruption. Canada had another robot, funnier than the Japanese one. Italy showed innovative automotive designs minimizing drag. The Philippines featured a restaurant overlooking Second Creek, and the whimsical, charcoal-powered bus, a replica of the famous Jeepneys of Manila, which sometimes toured the grounds.

Egypt, in the first year of the presidency of Hosni Mubarak, had agreed to come to Knoxville just four months after the assassination of Anwar Sadat. Their pavilion, almost entirely cultural, featured a museum-like experience with stone artifacts from the era of Queen Hatshepsut, as well as later eras. It was claimed to be the first-ever exhibit to show Egypt’s pharaonic, Coptic, and Islamic history in one place. Almost as big as the museum was a large gift shop of King Tut-style jewelry.

Peru had reportedly never participated in a World’s Fair, and its presence was politically delicate considering its strong alliance with Argentina in the Falklands war with the UK, which had started four weeks before the World’s Fair opened. But, half a mile from the UK pavilion, Peru ignored politics, displaying ancient Incan gold objets d’art, and a real centuries-old Incan mummy. Its controversial unwrapping before “an invited audience of 450” was claimed to be the first such procedure ever held in North America.

The Fair’s most futuristic national pavilion was that of the United States, celebrating solar energy, with a solar collector atop the unusual ultramodernist building and a waterfall meant to symbolize the potential of hydro energy. But the medium may have been the primary message. Designed and engineered by Carlos Ramirez and Albert Woods of New York, the pavilion’s educational features were electronic devices most Americans had never seen before, featuring multiple computer displays, including some featuring touch-screen technology, which would not be familiar to most consumers for years to come. Highlighting work from the Media Lab at MIT, the pavilion employed 30 Apple II personal computers, 50 Sony Videodisc players, and 25 Elographics Touch Sensors.

At the time, most Americans had probably seen personal computers in office settings, but didn’t have them at home. Videodisc technology was fairly new. And hardly anyone had seen touch-screen computers. Although many visitors hardly noticed them, and few reporters mentioned them, that may have been the most significant technological innovation featured at the fair. One rare exception was Rex Reed, who mentioned this “one interesting sidelight,” a wall of experts discussing energy via TV monitors that “could be changed just by touching your hand to the screen.” He’d never seen anything like it—“but when I asked for a demonstration nobody was around who knew how the damned thing worked.”

Touch-screen technology would become familiar to American consumers more than a decade later.

The most unlikely pavilion was by far the most popular, and in retrospect the most significant. Every morning, thousands stampeded toward the China Pavilion, where lines sometimes stretched all the way across the pedestrian bridge above Cumberland Avenue, sometimes rendering a wait of four hours. Inside, visitors saw dozens of skilled artisans at work, and around the corner were exhibits of nearly unearthed archeological treasures, including several 2,000-year-old terra-cotta warriors, and assembled bricks of the Great Wall.

Like its neighbors Egypt and Peru, late commitments who were allowed to gloss over the energy-science mandate observed by the others, China presented a mostly cultural exhibit, with an attached restaurant, and more than 100 staffers, few of whom spoke English.

***

Those paying close attention glimpsed some cultural icons.

Young bluegrass mandolin virtuoso Ricky Skaggs was only 27 when he performed at the Tennessee Amphitheatre; he joined the Grand Ole Opry the same year. Martina Navratilova was a rising tennis star of 25 when she competed in some exhibition matches at nearby UT.

At next-door neighbor Neyland Stadium, the fair hosted a National Football League exhibition game, on August 14, pitting the Pittsburgh Steelers against the New England Patriots. The crowd made more news than the Steelers’ victory: with 93,251 attendees, it was a bigger crowd than most Super Bowls, and considering that no NFL stadiums were as big as Neyland, in fact the fourth-best-attended NFL game in history. The Steelers’ star, 33-year-old quarterback Terry Bradshaw, was present, but disappointed the crowd by opting not to play.

Among those who visited the fair were Jimmy Carter and his daughter, Amy, who visited the Egypt pavilion near the anniversary of the death of his friend Anwar Sadat; the Georgia alt-rock group the B-52s, and boxer Sugar Ray Leonard, who made a point to see the China pavilion; Jerry Lee Lewis, who played an impromptu lunchtime set on the piano at the Strohaus; mystery bluesman Leon Redbone, who toured the fair wearing his white suit and shades, never breaking character, for hours before his show at the Amphitheatre; Kenny Rogers, here for the premiere of his first theatrical movie, Six Pack, who was seen waiting in a line at the Tennessee Amphitheatre with everybody else—and Hassan bin Talal, the later to be controversial Crown Prince of Jordan, who said he was especially impressed with the U.S. exhibit. The only sitting foreign head of state to tour the fair was Ferdinand Marcos of the Philippines, with his flamboyant wife, Imelda, who visited the fair on other occasions.

Dozens of writers visited the fair to report on it, among them Kurt Andersen, Raymond Sokolov, Ivor Davis, E.J. Kahn, and Rex Reed. It’s tempting to claim the world’s fair might be historic just for this assemblage of prominent journalists, some of whom became more famous later, even if their most common approach was to make fun of the fair. Most of their potshots were superficial, and hardly any of them suggest they spent more than a day looking around.

***

The fair’s primary focus was sustainable energy, and taken as a whole, the international and corporate exhibits covered the gamut of state-of-the-art energy technology. Few visitors saw them all, but those who did would have seen demonstrations of uses of natural gas, America’s shale-oil potential, the UK’s mechanized coal-mining innovations, Italy’s experimental nuclear fusion reactors, GM’s lightweight cars with plastic bumpers and aluminum engine blocks (still a promising rarity, 40 years later), Japan’s attempts to use geothermal technology safely, along with research into using trash, tar sands, and charcoal for practical energy.

If the fair offered no obvious breakthroughs that changed the world of energy, it elicited some earnest discussion in that regard. Beginning 18 months before opening, the fair’s organization hosted a series of Energy Symposia, most of them at the Hyatt Regency. The first one, a three-day event in October, 1980, including speakers from Finland, China, and the Soviet Union (Igor Makarov the science attaché claimed to be impressed with the conference; his appearance may represent the USSR’s only participation in the fair), as well as former National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy (1919-1996), who introduced the symposium; officials from the Carter Department of Energy; and Alvin Weinberg (1915-2006), the legendary atomic scientist from Oak Ridge.

A second conference in November, 1981, drew more major speakers, including Canadian-born author and nuclear engineer David Rose (1922-1985), of MIT; and Sweden’s Sigvard Eklund (1911-2000), in the final month of his 20-year term as director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency, who criticized Israel’s recent attack on an Iraqi nuclear plant. Raising questions about nuclear energy was Amory Lovins, who would be much better known in years to come, as a MacArthur Fellow and a much-honored author of several books about alternative energy. The safety of nuclear energy was a major subject in 1981, but the subject of biomass, the plant-based renewal alternative fuel, was a more novel topic of discussion.

Symposium III, held soon after the Fair opened, in late May, 1982, got the most attention, because of its celebrity power: among the speakers were scholars from major universities as well as Imelda Marcos (b. 1929) of the Philippines, U.S. Secretary of Energy James Edwards (1927-2014), former U.S. senator Al Gore Sr. (1907-1998), and maverick industrialist Armand Hammer (1898-1990). With nine detailed papers on energy policy from nations around the world, there was an emphasis on the necessity of global cooperation. One specific subject of discussion was the prospect of shale oil, which would be a major subject of exploration in the decades to come. The closing remarks, by Secretary Edwards, former governor of South Carolina, were delivered in public, at the Tennessee Amphitheatre. With little reference to the global energy issues discussed by the scientists at the conference, Edwards may have startled attendees with his assertion that his own energy department was unnecessary—and, looking forward to a future of expanded oil and coal production, that the secret to America’s energy independence was deregulation. Secretary Edwards resigned his post later that year.

Most of the discussion was about energy supply and demand and barely touched on environmental hazards, but at a later, environmentally themed energy symposium at UT campus that August, the speakers included author Edward Passerini (1937-2020), whose book The Curve of the Future would be much discussed about a decade later. But the most dramatic and sobering speaker may have been Knoxville’s own S. David Freeman (1926-2020), the TVA chairman, who was also an author and energy advisor to four presidents, who warned about the effects of a likely “scenario for total havoc” if the environmental effects of energy-related combustion weren’t curtailed.

The papers presented at the first three symposia were compiled in a three-volume set called World Energy Production and Productivity. An estimated 200 copies of that 1,000-page set are in libraries around the world. The Symposia dealt in detail with specific energy problems and potentials in dozens of different nations around the world. It might take years of research to determine whether anything presented at the conference had a significant impact, but the intention and scope of the series were impressive.

The technologically impressive painting robot delighted crowds at the Japan Pavilion. Courtesy of Paul Holzschuher.

The 1982 World’s Fair was a showcase for nations at a turning point, and each pavilion told a different story. The fair marked one of the most public gestures of China’s entry into the Western economy, which would be a major reality for the world in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. China’s role in the global economy, barely perceptible in 1982, has become dominant.

Although Hungary was still under Soviet domination, it had already been opening its economy under the comparatively liberal rule of Janos Kodar, and seemed to presage the future of its neighbors in the still-Communist eastern bloc. Hungary celebrated both composer Bela Bartok and the Rubik’s Cube, probably the most popular consumer product ever to emerge from beyond the Iron Curtain. On the other hand, the mere absence of the Soviet Union may be seen as one of the last vestiges of the Cold War.

Japan’s pavilion was a friendly testament to the technological and economic triumph of a nation defeated 37 years earlier. The Saudi Arabian pavilion was an acknowledgement of the continuing reality of the West’s need for Arab oil. The EEC exhibit, puzzling as it may have been to most, presented a promise that the future would include a European economic union. The United Kingdom’s participation was sometimes overshadowed by news of the Falklands war, but on June 21, they closed the pavilion for a special party to celebrate the birth of a royal baby, who would be known as Prince William.

In late summer, crowds diminished dramatically, and some services were curtailed by the budget-conscious KIEE that wanted to avoid the fair being remembered as a financial loss. By late October, the fair received its predicted 11 millionth visit, and when it was all said and done, accountants officially reported that the fair had made a profit of $57—though the city was still deeply in debt, especially for the investment in the site.

When the World’s Fair closed on Oct. 31, hardly anyone noticed it was Halloween. There was dancing at the Court of Flags, led by the star couple, Jake and Sonya Butcher. And then it was over.

Most of the exhibits and pavilions, built with corrugated steel or aluminum, were quickly disassembled, many of them to be reused for other purposes elsewhere, leaving only the historic buildings and the Holiday Inn, the Sunsphere, the Tennessee Amphitheatre, and the U.S. Pavilion and its IMAX Theater, for which many Knoxvillians had fond hopes for a future attraction. For several years, Hungary’s oversize facsimile of a Rubik’s Cube, remained on a pedestal near Clinch Avenue, frozen in mid-turn.

The World’s Fair’s anticipated improvements to its host city were not immediate. In fact, in a fragile downtown, where members of Evans’ Downtown Knoxville Association were expecting the old cafes to be flooded with tourist trade, the fair months were an anticlimactic disappointment. Historians might have predicted that outcome: at one of the world’s most famous fairs, the one in Paris that produced the Eiffel Tower in 1889, it was reported, “The shopkeepers, the restaurant keepers, the theatrical managers find that the show drains the boulevards, and that their business is reduced in a manner unknown since the siege.”

Almost all of Knoxville’s downtown businessmen experienced the same phenomenon. Not only did the fair not bring many new customers, it tempted downtown’s regulars away.

The fair preparation was said to have solved the “malfunction junction” tangle of interstate highways in the central part of town, but problems remained for many years to come, and interstate redesign and construction in the downtown area was a near constant for a quarter century after the fair.

Three new hotels had been built downtown in preparation for the fair; over the next two decades, city leaders sometimes despaired of keeping them in business. Knoxville in fact suffered a significant loss in population in the 1980s, worse than at any time since the 1950s.

And just three and a half months after the fair’s end, federal agents descended on the banks operated by Jake and C.H. Butcher, finding evidence of massive bank fraud. It was reportedly unrelated to the financing of the fair, but Jake Butcher had been such a personal symbol of the fair, that people naturally associated the two.

However, in 1982 Knoxvillians had made a habit of coming downtown at night, and some didn’t want to give that up, just because there was no longer a world’s fair to attend. An annual festival called Saturday Night on the Town, an outdoor musical multi-genre festival of the mid-’80s, became the most popular downtown street party in memory. Sometimes seen as an indirect result of the fair is the Old City. The abandoned warehouse district was little known by that name before early 1983, when English immigrant Annie Delisle, the former professional singer and dancer who had greeted crowds at the fair, opened her unusual continental restaurant, Annie’s, there. Other attractions followed, and by the late 1980s, the Old City was Knoxville’s most popular nightclub district.

Two residential conversions, the Pembroke and Kendrick Place, had opened in anticipation of the fair, and remained occupied, but the Candy Factory, promised as a post-fair condo development, remained empty. Residential development downtown didn’t begin to expand significantly until 15 years after the fair.

“The World’s Fair Site,” as it was known for 20 years, saw a variety of proposals, some well-considered, others farther afield. Meanwhile, the open, unbuilt parts of it found use for modest purposes, like Cherokee powwows, which sometimes took place in the Court of Flags area, and the Brewers’ Jam, the first-ever Knoxville beer festival—as well as occasional concerts and music festivals, either at the Tennessee Amphitheatre or the nearby South Lawn.

By 1985, the fenced-off Candy Factory seemed a symbol of lost momentum. Only later, it became a city-subsidized arts center—and later still, a residential condo development, as was originally promised.

However, in 1990, the Knoxville Museum of Art found a site where the old Japan Pavilion had been. It was one of the last designs of noted architect Edward Larrabee Barnes (1915-2004), who chose distinctive Tennessee marble to face it.

Fort Kid, the elaborate playground adventure, opened soon after the KMA, near where the European pavilions had been, and remained a popular attraction for 20 years before its removal. The Strohaus became the Foundry, a perennial event space.

The U.S. Pavilion, meant to be permanent, hosted a wild variety of events after the fair, from a mayor’s art auction to an ecumenical “Heritage and Faith Celebration” to an annual Chili Cook-Off. After several elaborate proposals for museums, energy-research centers, or international trade centers, it was labeled a “white elephant.” One of its main problems, ironically, was that it was not energy efficient. It and the IMAX theater were finally dynamited away in April, 1991.

Most of the fair site remained public space, except for the southern end, between Neyland Drive and Cumberland Avenue, which was acquired by the University of Tennessee for surface parking—though the city’s Second Creek Greenway connected the areas that had been the grounds of the Australia, Canada, China, Peru, and Egypt pavilions and the Family Fun Fair. The long-neglected riverfront soon became the site of Volunteer Landing’s greenway, which in the decade just after the fair, connected downtown to the existing Third Creek Bike Trail.

The city finally sited its long-discussed Knoxville Convention Center on the eastern side of the fair site in 2002, and at the same time, created an architecturally relandscaped World’s Fair Park across the northern portion of the fair site.

Forty years later, the humble Petro remains the basis for Petro’s Chips and Chili, which has about 30 locations in the mid-South, still run by the family who launched the oddity at the fair.

As for the fair itself, it has rarely been referenced in histories or biographies. The world seemed to forget the 1982 World’s Fair quickly. One exception is Chinese travel journalist Liu Zongren’s Two Years in the Melting Pot (1988). In the context of a tour of the United States, he described spending a few weeks in Knoxville with Chinese pavilion staffers. His assessment of Knoxville as a quiet and beautiful place contrasted with that of most American journalists. (His description of the Tennessee River is briefly quoted in a marble marker on Volunteer Landing.)

If the fair’s intent was to acquaint America and the rest of the world with ways to use less fossil fuel, its success is hard to prove. According to various data, U.S. per-capita consumption of oil has declined about 6-10 percent since 1982—but it actually rose for several years after the fair, and didn’t begin to decline until 2007, perhaps as a result of automobile efficiency improvements and the growing popularity of hybrid and electric vehicles. They were, at least, hinted at during the fair. Likewise, coal consumption continued to rise after the fair, and didn’t fall until 25 years later, but is now much lower, per capita, than in 1982.

Wind energy, hardly more than a dream in 1982, but demonstrated with Australia’s conspicuous windmills and U.S. demonstrations elsewhere on site, was, according to Mechanix Illustrated’s assessment of the fair, “a great idea whose time has not yet arrived.” Now wind accounts for a significant 5 percent of U.S. energy.

Perhaps most dramatically, U.S. nuclear power generation, a major theme of multiple exhibits at several pavilions at the fair, and of the Energy Symposium discussions, has almost tripled in the 40 years since, though questions of its safety remain, as do the challenges of waste disposal discussed at the fair.

The 1982 World’s Fair told so many stories it may take more than 40 years to assess them all, in the ever-changing landscape of energy and technology development. Things that seemed merely odd and mostly unmemorable sideshows in 1982—including touch-screen computers, electric cars, shopping and banking online, and teleconferencing—have become a familiar reality in 2022. As has the presence of the once-exotic nation of China and the European Union, and the reality of wind power. Perhaps future generations may hear of other reasons that back in 1982, maybe some history was made in Tennessee. Even if it wasn’t the history we expected.

By Jack Neely, April 2022

A PDF version of this essay by Jack Neely can be obtained on request. Please email paul@knoxhistoryproject.org.

This narrative was taken from a limited edition booklet published in May 2022 and funded by a generous grant from:

Appreciation goes to the following project partners for their contributions to this retrospective on the 1982 World’s Fair during its 40th anniversary.

Ernest Freeberg, Shellen Wu, Chad Black

University of Tennessee, History Department

Lisa Oakley, East Tennessee Historical Society

Todd Steed, WUOT-FM

Eric Dawson, McClung Historical Collection